17 February 2026

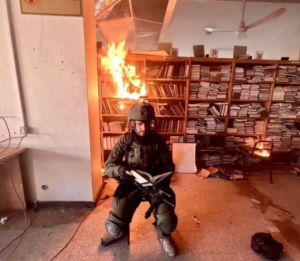

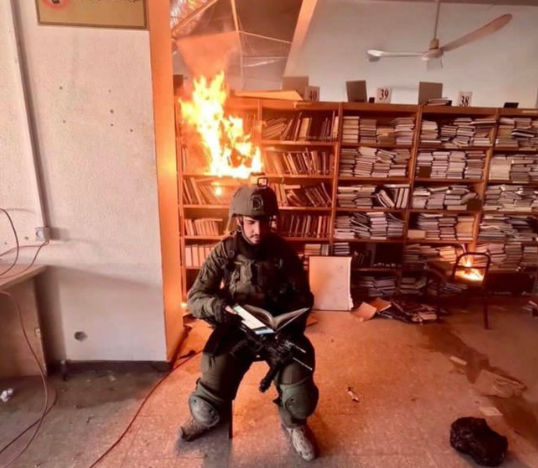

The following is a brief history of academic boycott from the French vantagepoint by a vice-president of AURDIP, the Association des Universitaires pour le Respect du Droit International en Palestine, BRICUP’s sister organisation in France. As Professor Ekeland describes, the French government has been as dogged in its opposition to academic boycott as recent British governments. The illustration, by the way, depicts an Israeli soldier who has just set alight the library of Al Aqsa University in Gaza.

The academic boycott of Israel

Posted on | Ivar Ekeland | YAANI

source

From the first invasions of Lebanon in 1982 to the recent assaults on Palestinian universities, the academic boycott has emerged as a form of nonviolent resistance to the occupation and militarization of Israeli higher education. Supported by many intellectuals and academics, the movement denounces the links between universities, the arms industry and violations of international law.

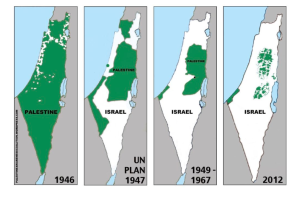

The invasion of Lebanon in 1982, the first and second intifadas, unleashed in 1987 and 2000, the successive invasions of Gaza in 2008, 2014 and 2023 have revealed to the whole world the disproportionate use of force to which the Israeli army is accustomed, and exposed the reality of occupation and colonization. It was in 2004 that a group of Palestinian intellectuals launched a call for an academic and cultural boycott (PACBI), and in 2005 that 170 organizations, representing all Palestinian civil society, launched a call to boycott Israeli products, to divest from companies contributing to the occupation and to sanction Israel (BDS).). The ongoing genocide in Gaza has given a boost to the movement, but has also revealed European fractures. While universities in the Global North and South, from Norway to Spain to Ireland, are freely deliberating to sever ties with Israeli universities, and many are doing so, in France, the United Kingdom and Germany, governments are using anti-terrorism legislation and the pretext of anti-Semitism to crack down on Palestine solidarity movements and ban debate in universities. The Prime Minister’s speech at Sciences Po in 2024 and that of the Minister of Higher Education at the Collège de France in 2025 have shown that in France, the government is watching institutions like milk on the fire, and has no intention of allowing an academic boycott to take place.

Legitimacy and legality of the boycott

However, the boycott is a non-violent and perfectly legitimate means of action. Its legality, as far as Israel is concerned, was confirmed by a 2020 judgment of the European Court of Human Rights, reversing previous convictions from French courts. It builds on a long and heroic tradition of resistance by Indigenous peoples in the face of colonizing power. The very name comes from an episode of Irish resistance to the British landowners (1880), and the boycott, under the aegis of the Swadeshi movement, was one of the means used for the liberation of India. Closer to home, the bus boycott in Montgomery in 1955 was a founding moment of the civil rights movement in the United States. We also remember the South Africa boycott movement, launched in 1959 in London, which contributed so much to the dismantling of apartheid.

In the case of Israel, the boycott is all the more legitimate because it is based on decisions of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the International Criminal Court (ICC), the highest international courts. In an order dated January 26, 2024, the ICJ declared the risk of genocide underway in Gaza “real and imminent,” and on May 20, 2024, the ICC issued arrest warrants for the Prime Minister of Israel and his Minister of Defense, for crimes against humanity and war crimes. Beyond the simple moral obligation not to be complicit in such crimes, these decisions create legal obligations towards all states, including the EU and therefore France, which have the obligation, for example, not to sell arms to Israel. These obligations extend far beyond arms sales: in an opinion issued on 19 July 2024, the ICJ declared Israel’s presence in the Palestinian territories occupied in 1967 illegal and stated that all states are under an obligation not to recognise this situation and not to support it either directly or indirectly, which naturally implies not trading with Israeli entities that maintain it. In short, the boycott of Israel is now a legal obligation for states.

“The boycott is a non-violent and perfectly legitimate means of action. Its legality, as far as Israel is concerned, was confirmed by a 2020 judgment of the European Court of Human Rights, reversing previous convictions from French courts. »

However, Western governments refuse to do so. They want to sanction Russia for having attacked Ukraine, they refuse to sanction Israel to prevent genocide in Gaza. This is not surprising: the lesson of history is that boycotts are systematically met with hostility from the authorities in place. For twenty years, between 1960 and 1980, when the United Nations called for economic sanctions against South Africa and an embargo on arms destined for Pretoria, the American and British governments opposed it, President Reagan in the name of free trade and the fight against communism, Prime Minister Thatcher in the name of the well-being of the populations subjected to apartheid, According to her, the first victims of the sanctions. Recall that in 1989 the United States ranked the ANC, Nelson Mandela’s party, as one of the 52 most dangerous terrorist organizations in the world, alongside Fatah and Hezbollah, and that Nelson Mandela himself was on the “terrorist watch list” until 2008, four years after he announced his retirement from public life.

As for Martin Luther King, it was from the depths of a Birmingham prison that he wrote his famous letter to eight white clerics, of all faiths, who had described his struggle as “unwise and untimely“, that is to say, misguided and ill-timely, and called him, and those who had come to assist him, “outsiders coming in people who interfere in an internal debate where they had nothing to do. One cannot help but think of the current rhetoric directed against demonstrations of solidarity with Palestine, accused of stirring up anti-Semitism at a dangerous time, and the injunctions not to “import” the Israeli-Palestinian conflict into France.

Boycott Israel

We always talk about the economic impact, and it is true that in the case of South Africa, it has been significant. But it seems to me that the main purpose of the boycott, in the case of Israel, is educational: to make known what is happening. For years, people were made to believe that there was a peace process underway, that things would settle themselves, that they should not get involved, and that those who did so were troublemakers. The purpose of nonviolent action, and in particular of the boycott, is to make them understand that this is not true, that things are not moving forward, quite the contrary, that things are going from bad to worse. When you refuse a Teva product at the pharmacist’s office, it’s an opportunity to explain why and talk about colonization. When we ask for an end to academic cooperation with Israeli universities, we justify the request by explaining what the military-university complex is in Israel. When we go to Brussels to demand that Israel no longer participate in European research programmes, we present a dossier showing how certain projects financed by our taxes are used to facilitate the occupation, by replacing human surveillance with artificial intelligence or by contributing to the massacre of innocent people, by developing weapons that will be tested in Gaza before being sold on the international market. The boycott is a way to break the wall of silence maintained by the mainstream media and the GAFA on what is happening in Palestine and to bring the Palestinian question into the public debate. It is by shifting opinion that our governments will be forced to stop exporting arms to genocidaires or to interrupt the preferential status granted to Israel by the European Union, as required by international treaties and as required by the ICJ rulings.

These boycott actions are part of a global movement, BDS, which goes a long way to demonstrating its political and non-discriminatory nature. This movement takes different forms depending on the country and keeps an up-to-date list of products and companies to be boycotted, while giving the reasons for this. For example, there are products labelled “made in Israel” which in reality come from the settlements, and companies such as Carrefour which have franchise agreements with certain Israeli companies that serve settlements. From the beginning, BDS has had an academic and cultural component, PACBI. The PACBI maintains a series of guidelines on academic and cultural boycotts, based on the general principle that boycotts are about institutions, not individuals: “PACBI rejects as a matter of principle any boycott of individuals on the basis of their opinion or identity (such as citizenship, race, gender or religion)”. As far as institutions are concerned, all Israeli universities are targeted, as well as cultural institutions that do not publicly recognize the inalienable rights of the Palestinian people and do not cease all forms of complicity in the violation of those rights. In practice, this leaves room for a wide variety of interpretations and many grey areas. PACBI is far from being hegemonic and campaigns vary from country to country, but a basic principle has emerged: we boycott institutions and not people.

Why universities?

This is because Israeli universities are not collectives of disinterested souls who commune in the search for truth. From the first to the last, they were conceived as instruments of colonial policy, serving to appropriate the land and enslave the indigenous population.

In 1918, a Jewish university was founded in Jerusalem, to the sound of “God save the king“, nestled between Palestinian villages, while the British had always refused the creation of an Arab university. Now the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (UHJI), it was to extend after the Nakba of 1948 on the ruins of the Palestinian village of Sheikh Badr, whose inhabitants had been driven out by the Haganah, in a strategic position that largely contributed to the Judaization of East Jerusalem after the conquest of the city in 1967. This policy of territorial implantation has been pursued by all Israeli universities. The latest is that of Ariel, built in 1982 as an annex of Bar-Ilan University, in the middle of the occupied West Bank, in defiance of all international commitments and to the great displeasure of the Palestinian population, and erected as a university in its own right in 2012.

Israel is an arms dealer. Israeli companies, Rafael, Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI), Elbit, which are the pride of the country, are in the top 100 of the world’s arms manufacturers. In this market, where Israel competes with heavyweights such as the United States, Russia and China, not to mention France, the country ranks tenth with a 2.4% market share. This is no coincidence: it is a deliberate strategy in which universities play a key role. There is no equivalent in Israel of the CNRS or the École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr: it is the universities that fulfill these roles of fundamental and applied research, and training of the military. In 1946, the Haganah mobilized students and researchers from the three universities of the time (UHJI, Weizmann Institute in Rehovot, Technion in Haifa) within the Science Corps, which was set up on the three campuses. In 1958, the Science Corps became Rafael, which was based on the skills, training and research programs, and students of the Weizmann Institute and the Technion. In 1954, the Technion opened a Department of Aeronautical Engineering which became IAI. As for Elbit, its president Michael Federmann declared in 2008 that “the Technion is woven into Elbit’s DNA” [1]. All of these companies have a presence on campus, where they offer internships and training to students.

“The interweaving between Israeli universities and the army goes far beyond mere assistance with equipment and training, to ideological complacency, to incitement to genocide.”

In addition to territorial control and participation in the war economy, Israeli universities directly train the military. One example is the UHJI’s Havatzalot program, which is designed to train officers in the Intelligence Corps, the spy service. Tailor-made according to the wishes of the military authority, the program includes a bachelor’s degree in Middle Eastern studies, carried out at the university with civilian students, as well as training in practical ways of extracting information, carried out in the field among the occupying troops. Palestinian students enrolled in Middle Eastern Studies therefore have the pleasure of attending classes and discussions in the presence of uniformed soldiers who intend to spy on them. This situation had not escaped the attention of the teachers, and in 2018, when the program was installed, some of them had expressed the intention of organizing a round table to discuss its implications for the University. The administration said it would consider this an “internal terrorist attack,” and the event was moved [2].

The interweaving between Israeli universities and the army goes far beyond mere assistance with equipment and training, to ideological complacency to incitement to genocide. On November 7, 2023, a month after the October 7 massacre, Professor Porat, president of Tel Aviv University, gave a speech in which he said: “Remember what Amalek did to you during your journey, when you left Egypt: this is what Devarim’s book teaches us. And then there is the divine command to the people of Israel: You will blot out the memory of Amalek from under the heavens. Remember. This is what must be done with Hamas, and I am convinced that this is what the State of Israel will do.” If one consults the sacred texts, in particular 1 Samuel 15, it is indeed a call for genocide, as South Africa did not fail to point out in its complaint against Israel to the ICJ.

What is the impact of this academic boycott?

According to a report commissioned by universities and relayed by the Israeli press, while the academic boycott was anecdotal before 2023, the genocide in Gaza, accompanied by the destruction of universities and the targeting of Palestinian teachers, has turned it into a movement that now threatens the military-university complex. Contrary to their expectations, the signing of the pseudo-ceasefire has not slowed it down, with the number of reported cases doubling between March and November 2025. These range from boycotts that do not say their name, researchers working for Israeli universities who discover that they are no longer invited to conferences or who have more difficulty obtaining European funding, to declared boycotts. The University of Naples Frederick II, the oldest secular university in Europe, has just declared that it no longer cooperates with Israeli institutions, joining some 50 European universities in Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Belgium, Ireland, Switzerland and Norway that have, to varying degrees, re-examined their ties with Israeli universities.

In France and the United States, on the other hand, the movement has been stifled. We know what is happening in the United States, where presidents have been forced to resign, students have been deprived of degrees or expelled from the country, and the most prestigious universities have been forced to review their programs. France followed suit, in a less conspicuous way, and brought its universities to heel. The students who protested in 2024 were punished, examples were made among the researchers and teachers who supported them, and the result is that the campuses are calm, even dead. The question is no longer to boycott Israeli institutions, it is to ensure the survival of authentic knowledge about the colonization of Palestine, based on historical facts and field investigations, and this is not easy, as shown by the ban on the conference “Palestine and Europe” at the Collège de France last November.

Not content with controlling what is said in universities, the government claims to control who they talk to. In an opinion issued by the Ministry of Higher Education and Research, it is written that “the precedent of the war in Ukraine cannot be invoked to justify the questioning, by French higher education institutions, of partnerships concluded with other States located in areas of armed conflict, since the suspension of relations with institutions located in Russia, following the invasion of Ukraine, was the direct consequence of government directives in this regard”. Indeed, a month after the Russian invasion, the presidents of French universities, without consulting their institutions, broke off all cooperation with the rectors of Russian universities in a statement that ignored “government directives” but argued that there were “unacceptable attacks against the civilian population and […] the deliberate bombing of public buildings, hospitals, student residences, or teaching and research premises”. After two years, the same presidents have not found a word to say about the genocide in Gaza, no doubt waiting for these famous “government directives”.

We are dealing with a discipline of French universities which, in addition to ridiculing them, is undoubtedly the prelude to much more serious attacks. This shows that the struggle for the rights of the Palestinian people, including the right not to be massacred, can only be waged in a society that is itself free, if not completely, at least free enough to hear unpleasant truths. At the moment, the French government is incapable of listening to them: to environmental activists, to the yellow vests, to the ICJ orders, it responds with repression. But persecuting activists does not solve the problems: global warming, soaring inequality, and non-compliance with international law are preparing us for a hostile world, in which France risks sinking. It is time for our country to return to democratic functioning and for our government to once again be concerned with the public good, based, as everyone knows, on respect for nature and people, wherever they are, in France and in Gaza.

[1] Maya Wind, « Towers of Ivory and Steel », Verso 2024, p. 105

[2] loc.cit. p. 51

By Ivar Ekeland, former President of the University of Paris-Dauphine, Vice-President of the AURDIP.