4 December 2025

This excellent account in Jewish Currents provides a vivid picture of the ways pro-Israel activists and propagandists succeeded in turning the UCLA (University of California in Los Angeles) administration and public against peaceful pro-Palestinian protestors, which in turn led to gratuitous violence, the victimisation of students demonstrating for human rights, the suppression of free speech and severe damage to the University’s reputation. The Introduction by Editor-in-chief of Jewish Currents Arielle Angel, reprinted first, highlights the significance of the account.

2 December 2025

Dear Reader,

For all of my tenure as editor-in-chief at Jewish Currents, even long before October 7th, monitoring campus politics on Israel and Palestine has been core to our beat. Throughout the 2010s, as the pro-Israel establishment tried to stem the tide against BDS votes in student government, the Jewish mainstream already spoke of a “crisis” of antisemitism on the college campus. Among Zionists, conspiracy theories circulated that Palestine activists on campus enjoyed large amounts of outside money and support, particularly from Qatar. But as our reporting often reflected, building off journalist Josh Nathan-Kazis’s findings in The Forward, it was the other way around: Tens of millions of dollars were flowing into pro-Israel groups focused on the North American campus. Many, like Canary Mission or the Israel on Campus Coalition—aimed at doxing pro-Palestine students or astroturfing digital opposition campaigns to spook administrations—were largely operating without any student involvement. Groups like StandWithUs and AIPAC were training high school students to go on offense, turning students into effective lobbyists for the Israeli government who showed up to college primed to see Palestinian flags as an offense.

This state of affairs became all the more relevant over the last two years, as students in the Palestine movement on campus were maligned by news anchors and politicians, beaten and arrested by police, doxed by pro-Israel groups, and censured by school administrations. Yet despite this power imbalance, it seemed every other week The Atlantic had a new long-form piece ridiculing the students for their trendy activism or casting them as the horseman heralding the end of the golden age of American Jewry. Many of those who once protested the Vietnam War, some holding the flags of the Viet Cong, now cried out for law and order. On CNN, anchor Dana Bash drew comparisons to 1930s Germany, reporting news of arrests on campus in ways that took the arrests themselves as evidence of wrongdoing.

The video that sparked Bash’s comparison to the Reich was of a StandWithUs-trained activist and known provocateur at the University of California, Los Angeles, named Eli Tsives, who claimed he was obstructed from getting to class by encampment activists. But, as Will Alden’s reporting shows, Tsives was not blocked from his class that day; there were multiple open entrances close by. As UCLA Israel studies professor Dov Waxman told Alden, students “could simply walk around the encampment . . . The idea that Jewish students couldn’t enter UCLA, or couldn’t go to class, is just misrepresentation.” In other words, the video was a stunt. And it worked. The viral video is largely responsible for the broad perception that Jewish students were singled out and barred from their classes by Palestine activists.

This is only one insight in Alden’s astounding feature on UCLA from our Fall issue. Reported in the spring of 2025—a year after a pro-Israel mob sent dozens of students at the encampment to the hospital with serious injuries, while police watched—the piece, written in an engaging documentary style, offers a power map of the forces pushing policy on campus, and a post-mortem analyzing the seemingly permanent changes to campus life. As Alden dives into the epicenter of Zionist faculty activism at the med school; the world of pro-Israel student influencers; the interplay between the administration and the multiple police forces converging on campus; and the success of pro-Israel lawfare groups extracting concessions from universities, a portrait emerges of an environment in higher ed that has become decidedly more dangerous and less free for students exercising their First Amendment rights. We hope you’ll give this a read and share it with the people in your life who have been provoked in any direction by the campus dynamics of the last two years. I can say confidently that there isn’t anything in the media ecosystem like it.

Arielle Angel

Editor-in-chief

Portrait of a Campus in Crisis

UCLA capitulated to its own hardline pro-Israel activists long before President Trump came calling. As a result, its students have repeatedly become targets of vigilante and police violence.

This article appears in our Fall 2025 issue.

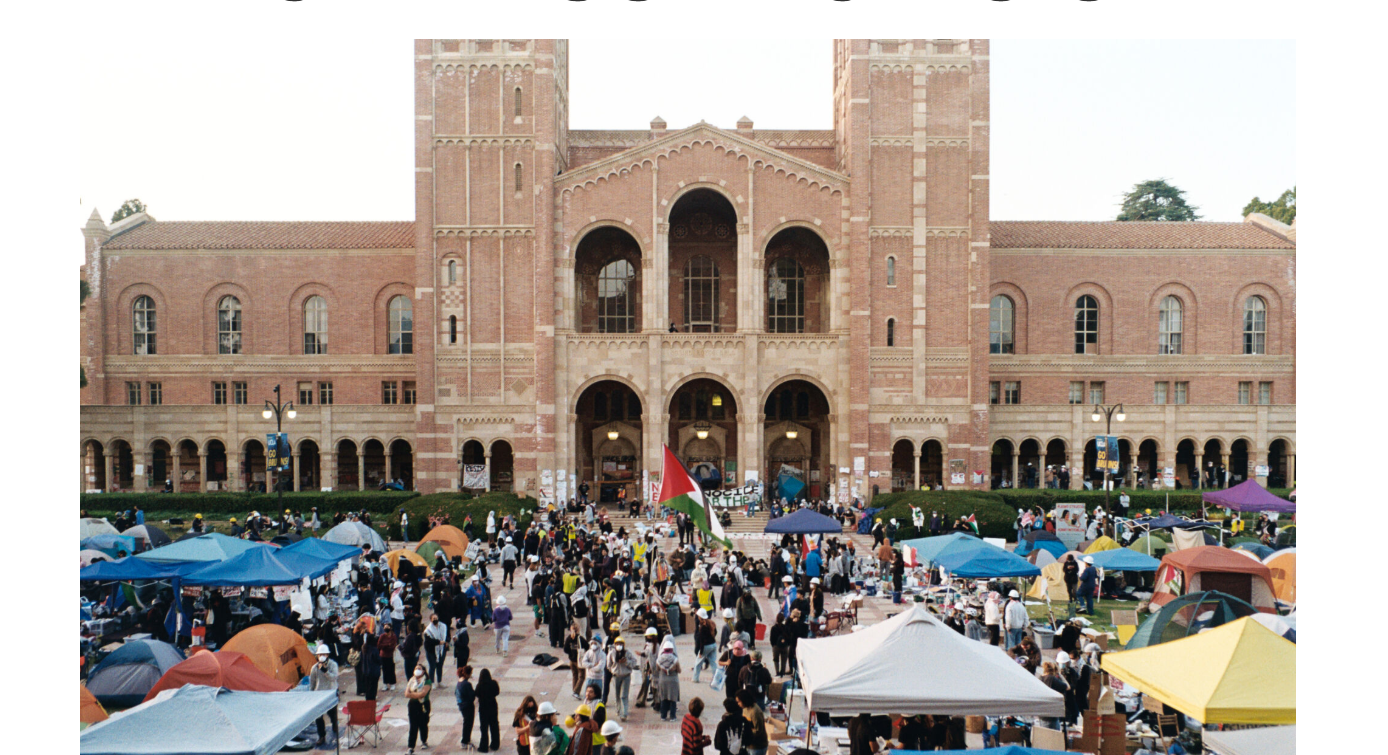

Around 8 pm on the last evening in April, some 200 people gathered in Bruin Plaza on the University of California, Los Angeles, campus for a screening of the documentary The Encampments. As the sky darkened and lampposts clicked on, members of the school’s chapter of Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) stretched a white sheet of fabric between two metal poles, while their comrades in flannels, puffer jackets, and loose-fitting jeans, most faces obscured by medical masks or keffiyehs, settled on blankets near the Bruin bear statue. The Encampments chronicles the Palestine solidarity movement at Columbia University, but it includes a brief portrayal, nearly 30 minutes in, of the UCLA students’ own encampment on Royce Quad, not far from this evening’s screening—the site where, exactly one year earlier, an off-campus mob wielding wooden boards, metal rods, fireworks, and chemical spray had staged a ferocious overnight attack while police looked on. Victims of that mob attack were among the crowd marking the grim anniversary, yet they never got to see their protest represented on screen. About 25 minutes into the film, a column of 30 University of California Police Department (UCPD) officers in riot gear emerged from behind a concrete stage at the northeastern edge of the plaza, marching two abreast, visors down, batons and pepper-ball guns in hand.

This aggressive interruption of the students’ movie night marked a new phase of the sprawling police operation that had dominated a section of campus for the previous week: UCPD officers from up and down the state—including the Riverside, San Diego, Santa Barbara, and San Francisco departments, in addition to UCLA’s own—had spent the days leading up to the anniversary of the attack patrolling Royce Quad and sitting in police SUVs prominently parked near the grassy expanse. The SJP students had originally planned to screen the documentary on the quad, but on the afternoon of the event, university security personnel sealed off the area with steel barricades, and a long caravan of California Highway Patrol SUVs pulled into a campus parking lot nearby. This expensive show of force, while unusual in its size, exemplified post-encampment UCLA, described by a group of faculty members in a May essay in The Nation as “a fortress” that was “nearly unrecognizable as a university.” In the wake of the 2024 mob attack—and the subsequent mass arrest of the student protesters who had been attacked—the university went to work “ensuring that the Royce Quad encampment and related incidents could never happen again,” including by redrawing its emergency-response plan so that police officials “no longer need[ed]” to consult senior administrators before curbing campus protests, according to a sworn declaration that summer by Rick Braziel, then head of the newly formed Office of Campus Safety. In the fall, under a preliminary federal injunction premised on the idea that the encampment had been a “Jew Exclusion Zone,” UCLA announced an interim update to its “time, place, and manner” rules, effectively limiting protests to certain “areas for public expression” and forbidding “tents, campsites or other temporary housing or other structures” anywhere on campus unless specifically approved by the Events Office.

The revision to these free-expression policies was widely viewed as unfairly targeting the Palestine solidarity movement, gathered under the banner of the UC Divest Coalition at UCLA. Campus authorities invoked the new rules in October, as they dismantled Jewish students’ solidarity sukkah, and again in November, when they arrested four people connected to a protest on Bruin Walk. When, on the evening of the Encampments event, the SJP activists arrived in their backup location—Wilson Plaza, down the steps from Royce Quad—with an inflatable screen, a Student Affairs official informed them that, “the second that thing goes up,” facilities workers and police would confiscate it: Apparently, the backyard movie rig qualified as an unauthorized structure. Rather than argue, the students packed up their equipment and directed the group to Bruin Plaza, one of the few designated “areas for public expression,” where amplified sound was allowed until midnight. Ditching the inflatable screen, they opted for a more DIY approach. “We thought, ‘Hey, we have this white bedsheet; let’s just have two people hold it,’” one of the screening’s organizers, a computer science graduate student named Dylan Kupsh, told me later. “It’s not a temporary structure because it’s not attached to anything.”

The audience in Bruin Plaza—including experienced SJP members like Kupsh who’d been keeping tabs on the police while the film played—were on their feet before the UCPD officers reached them. “We’re going to move together,” a student in a black “University of California Intifada” t-shirt and a keffiyeh worn as a hood said into the megaphone. “Together we keep each other safe, right? We keep us safe!” Their number dwindling, the students walked west until they reached De Neve Plaza, a courtyard surrounded by dorms. There, having lost the police, they encountered another familiar antagonist: Eli Tsives, a curly-haired sophomore, perched on a low wall and holding out an Israeli flag. A frequent counterprotester who had amassed a major Instagram following on the back of his post-October 7th advocacy—most prominently with an April 2024 viral video in which he portrayed encampment activists as “promoting hate” because they were blocking his preferred path to class—the 20-year-old Tsives had a proven ability to attract attention and push the administration to take a heavier hand with the student movement. In previous confrontations, the activists had been careful not to take the bait: Tsives’s own videos typically show them responding calmly to his finger-jabbing and bellowed accusations. But this time, just seconds after Tsives brought out the flag, someone snatched it and ran.

Tsives, in his muscle-hugging t-shirt and white Nikes decorated with Israeli flags, sprinted after, into the tide of arriving students, where I lost sight of him. “This person does not deserve our attention!” said a woman with a keffiyeh around her hair, urging others away. Soon, I watched Tsives shove his way out of the crowd. “Only Jewish kids getting assaulted right now,” he shouted, as if narrating for an audience. In the caption of the video he posted later, Tsives said the protesters were “violent” and suggested that they tried “to beat me up,” but the video itself doesn’t support this. Though the action is obscured, Tsives is shown roughly grabbing someone in a black hoodie and demanding his flag, while others in keffiyehs try to intercede. When I approached him afterward, he told me he’d been put in a headlock. Watching with arms crossed as the students set up their film equipment in De Neve, Tsives said, “I feel better than ever, because the police are going to come and get rid of them.”

The group of activists had just gotten the film playing again when the riot police appeared—breaking into a run as they entered the courtyard. The students stopped their chants of “Shame!” and fled. There were isolated screams as the officers, batons drawn, chased them up the steps outside the Dogwood dormitory, and as two motorcycle cops roared in from the opposite side of the courtyard, misery lights flashing. The police arrested the two people who had been holding the poles of the makeshift screen—one a student and the other an alumnus—and barred them from campus for two weeks, citing a Vietnam War-era law that the university unearthed last year and now regularly deploys against pro-Palestine student activists. The alumnus was sent to the emergency room that night with minor injuries to his hip, shoulder, and wrist that he sustained when the arresting officers pinned him against the concrete steps.

Tsives’s all-but-inscrutable Instagram video, promoted by pro-Israel accounts like Jew Hate Database and JewBelong, quickly became the latest flash point in a concerted campaign to paint UCLA as a hotbed of Israel-related antisemitism. The hardline Jewish Faculty Resilience Group at UCLA declared in a statement the next day that the film screening had “resulted in the violent assault of a Jewish student who had expressed support for Israel.” On Fox News @ Night, the anchor Trace Gallagher played Tsives’s video and pronounced him “the victim of an antisemitic attack.” The UCLA administration, in a statement, rushed in to apologize to the student (they did not identify Tsives by name) who had been “physically assaulted” on the night of the screening: “We are sorry for what this student experienced, and we have already been in touch with him to offer support.”

This kind of distortion was nothing new, Catherine Hamilton, a former editor at the Daily Bruin student newspaper, told me. But something about the anniversary of the mob attack added insult to injury. A year earlier, Hamilton herself was hurt while reporting; assailants sprayed a chemical into her eyes and hit her in the chest, causing pain in her sternum “so intense that she could not stand up,” according to a lawsuit filed in March against university officials, police agencies, and known attackers. Though the violence at the screening was smaller in scale, Hamilton seemed pained by the familiar pattern—the Zionist provocateur spoiling for a fight, the police gunning for pro-Palestine students, a protester taken to the ER, and the university adopting wholesale the narrative spun by pro-Israel actors. “It is, in many ways, just sickening,” she said.

Hamilton seemed pained by the familiar pattern—the Zionist provocateur spoiling for a fight, the police gunning for pro-Palestine students, a protester taken to the ER, and the university adopting wholesale the narrative spun by pro-Israel actors.

An “Exceptional Failure” to Protect Students

This is a story about UCLA in the long aftermath of October 7th, but its outlines could apply to any number of American universities embroiled in struggles over political speech that are rapidly remaking our democracy as we know it. The dominant narrative advanced on cable news and in every major American newspaper over the last two years is one of a crisis of campus antisemitism. In The New York Times or on CNN, the student movement has been represented not so much by its core demand—that universities divest from companies complicit in the grinding annihilation of Gaza—as by the emotional experience of Jewish students who feel upset by it. Students at Columbia created a buddy system “so that no Jew would have to walk across campus alone if they felt unsafe,” wrote Franklin Foer in an April 2024 cover story in The Atlantic; Jewish students’ account of “the fear that consumed them when they heard protesters call for the annihilation of Israel” led Foer to conclude that the university was “a graphic example of the collapse of the liberalism that had insulated American Jews.” This image of the Jewish student in peril was even projected internationally: “Every place you go around the world, you hear from Jews, and they’re worried about coming here to the United States, particularly to college campuses,” CNN host Jake Tapper said on air in December 2023.

This narrative—which tends to shift public attention to American fora and away from the abundantly documented atrocities in Gaza—has cast the most outspoken Zionists on campus as representative of Jewish students. There was the student at Yale who alleged that a passing protester “stabbed” her in the eye with a small Palestinian flag “because I am a Jew” (on Fox News the next day, her eye appeared unharmed); the Florida State University student in an Israel Defense Forces t-shirt who told police he’d been “hate-crimed” in the gym by a graduate student who said, “Fuck Israel, free Palestine,” before she allegedly grazed his shoulder while making a grab for his smoothie. Such stories, often accompanied by inconclusive video, catch fire online among those predisposed to read them as examples of antisemitism, even in spite of “scant details,” Arno Rosenfeld wrote recently in The Forward. They evince “a kind of spiritual truth rather than a detailed set of facts.”

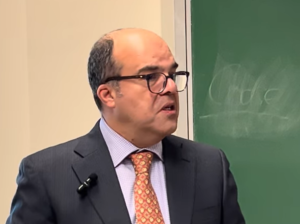

The students on this social media dais have become savvy ambassadors for a worldview, endemic to organized American Jewish life, that conflates Jewishness and Zionism. In his senior year of high school, for example, Tsives did an internship with the Zionist group StandWithUs, where, he told me, instructors taught him “not just Israel 101 but also everything that you need to know about how to hold an argument” with pro-Palestine activists in college. Even those young American Jews who do not attend such programs are often raised within institutions that instill in them a powerful identification with the Jewish state. “They’re taught that threats to unqualified support for Israel are threats to Jewish safety, and they take it to heart,” said Marjorie Feld, a professor at Babson College and the author of The Threshold of Dissent: A History of American Jewish Critics of Zionism.

Long before President Trump adopted the allegation of antisemitism as the central tool in his crusade against higher education, university administrators—under pressure from their donors and trustees and from activist members of Congress—have elevated even the flimsiest reports of harm to Jewish students as justification to tamp down on pro-Palestine activism. Despite video of the alleged eye stab depicting something far more ambiguous, Yale opened an inquiry into the claim and enlisted the help of the FBI in tracking down the flag-waving student; at FSU, the graduate-student worker who’d said “fuck Israel” on video was fired, suspended, barred from campus, and charged with misdemeanor battery. Universities have suspended clubs, fired teachers, and punished their own star students for speaking out against Israel. Their official task forces to study campus antisemitism, convened in the months after October 7th, were sometimes chaired by professors of dentistry, epidemiology, and real estate finance—nonexperts who happened to be Jewish and who produced credulous reports that relied on outside pro-Israel groups like the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) for their analysis. Yet even kowtowing, in televised grillings on Capitol Hill, to the notion that strident protest of Israel amounted to anti-Jewish hatred did not spare the presidents of Columbia, Penn, Harvard, and other universities their jobs.

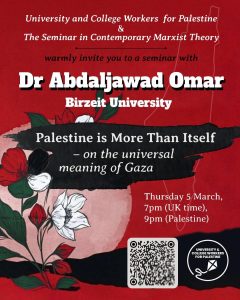

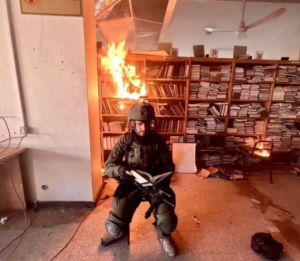

What it did, instead, was help pave the way for President Trump to attack the nation’s leading sites of critical inquiry under the cover of what movement strategist Sharon Rose Goldtzvik has called “smokescreen antisemitism.” In March, the same month that The Atlantic’s Foer released a follow-up article taking aim at Columbia’s “anti-Semitism problem,” the Trump administration canceled $400 million in funding for the university and, apparently acting on information provided by Zionist doxing group Canary Mission, sent ICE agents to detain Palestinian student activist Mahmoud Khalil. In April, the same month that The New York Times was amplifying the “scathing” report by Harvard’s task force on antisemitism, the Trump administration withdrew $2.2 billion in grants over diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs and alleged antisemitism at the university. Unlike Columbia, Harvard took the feds to court—drawing praise from liberal commentators—yet the university had already fulfilled parts of their demand list, dismissing the faculty leaders of its Center for Middle Eastern Studies (CMES) and suspending the research partnership between its school of public health and Birzeit University in the West Bank.

Indeed, the Trump administration’s wide-ranging assault on universities has been built upon the successful efforts of campus pro-Israel advocates, along with donors and outside groups, in lobbying for the illiberal and violent repression of pro-Palestine speech. Though Foer contended in his March article that the Trump administration was “exploiting the issue of anti-Semitism,” its demands of Columbia substantially echoed a previous list of demands by the university’s own Zionist faculty activists. Similarly, Harvard’s CMES and its partnership with Birzeit had both come under attack by an influential Jewish alumni group in a distortion-filled May 2024 report.

The crisis at California’s largest public university, while attracting less national attention than its Ivy League equivalents, has exemplified these dynamics. I spent the spring quarter visiting UCLA and interviewing more than 40 people—students, faculty, staff, and outside advocates on all sides of this drama—in an attempt to understand how these national political trends were playing out at a single university. The picture that emerges is one of a campus besieged from without and within, caught between the crusaders in the White House and those walking its own halls. Contrary to the ubiquitous narrative of Jewish victimhood, a sober look at the nation’s No. 2-ranked public university in this moment of fracture reveals that the power on campus overwhelmingly accrues to the most right-wing Zionist students and faculty in their efforts to stifle opposition to what United Nations experts call a genocide in Gaza. Theirs is a faction supported by well-resourced communal organizations and Trump-aligned law firms, and defended by police and the federal government. Successfully pushing their message to a sympathetic media and stoking the outrage of powerful allies, the pro-Israel advocates on campus appear more as agent than object, more doer than done to. Their concerted pressure campaigns targeting administrators have gotten results in the form of new, strictly enforced policies; disciplinary proceedings against protesters; interventions into academic curriculum; and the repeated use of police and other security forces to quell the student movement.

Contrary to the ubiquitous narrative of Jewish victimhood, a sober look at the nation’s No. 2-ranked public university in this moment of fracture reveals that the power on campus overwhelmingly accrues to the most right-wing Zionist students and faculty.

This activist infrastructure long predates October 7th, gaining steam over the last decade in response to boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) resolutions on campuses. A “complex landscape of many different campus groups” and donors, in the words of Josh Nathan-Kazis, the journalist who documented these efforts in a series of articles in The Forward in 2018, has collectively poured cash into “very aggressive, and very hard-nosed” strategies to counter campus activism. Nathan-Kazis pointed out in a 2019 interview that “this whole wave of hardline tactics and entities” did not come from Jewish students themselves, but rather “from ideas developed by think tanks in Israel, and leaders of the American-Jewish community.” This dynamic persists: When students in the UC Divest Coalition at UCLA established their encampment in April 2024, the Miriam Adelson-backed Israeli-American Council, the Jewish Federation of Los Angeles, and other groups quickly organized a rally on campus with the university’s permission, where Anti-Defamation League CEO Jonathan Greenblatt, draped in a combined American-Israeli flag, pointed to the nearby encampment and said, to cheers, “Their evil and their fascism will not win.” The backdrop to the rally stage was a “Jumbotron” TV screen erected by an off-campus group calling itself the Bear Jews of Truth and paid for by a list of prominent donors, including Jessica Seinfeld, a cookbook author and the wife of comedian Jerry Seinfeld; Bill Ackman, the hedge-fund billionaire who has gone to war with Harvard over its student protests; and a host of local machers in real estate and law. The intention for the screen, according to archived versions of the GoFundMe page, was to create a “legendary counter move” to the encampment, drowning out student chants by playing “nonstop clips” of “the screams and cries of October 7th.” In the wake of the mob attack two days later, Jewish student leaders at the campus Hillel—who self-identify as Zionists—wrote in a pointed statement, “We can not [sic] have a clearer ask for the off-campus Jewish community: stay off our campus. Do not fund any actions on campus. Do not protest on campus. Your actions are harming Jewish students.” Of the Jumbotron, they wrote, “We can’t learn over the constant noise of Jews being slaughtered.” Yet even if the Zionist activists, like Tsives, represent only a fraction of Jewish students, they style themselves as the embattled avatars of UCLA Jews in general and are often adept at flexing the power arrayed around them. In our first interview, in April, Tsives described the network of organizations operating on campus as a “Jewish powerhouse,” adding that the new chancellor, Julio Frenk, who was “brave enough” to suspend SJP in his second month on the job, had provided “that final cherry on top.”

At UCLA, fearmongering by outside groups and their allies on campus eventually led to violence. Out-of-context audio and video clips like Tsives’s—promoted by members of the Jewish Faculty Resilience Group, by then-Chancellor Gene Block in a widely circulated statement, and by outside groups including the Maccabee Task Force and the Israel on Campus Coalition—spread through local group chats including Persian Jews of LA, Israelis of LA, and Beverly Hills neighborhood groups. In the ensuing hours-long attack on April 30th, at least 25 activists from the encampment were rushed to the ER with blunt-force head traumas, fractures, lacerations, and chemical-induced injuries, while more than 150 required on-site treatment for pepper spray and bear spray, according to a report by volunteer medics. “I thought I was going to die. I thought I’d never see my family again,” one student, who was hit in the head twice and received stitches and staples in the hospital, told Hamilton in her Daily Bruin report. Thrust into an international spotlight, UCLA administrators answered this assault on their own students by directing the California Highway Patrol, armed with riot guns, to clear the encampment the following night, resulting in additional injuries and 209 arrests. In allowing “people who violently disagreed with the political message of the encampment to dictate the terms of the protest,” the university submitted to a “heckler’s veto,” as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) contended in a lawsuit, and “trampled” on students’ right to free expression. In the weeks following, and into the next academic year, the university adopted a muscular new approach to enforcement, with the police continuing to arrest student protesters, send them to the emergency room, and temporarily ban them from campus. In the last two years, roughly 130 students have faced disciplinary charges related to pro-Palestine activism, with some of them charged multiple times, according to faculty and staff supporting their defense.

Now, like other schools, UCLA has responded to the Trump administration’s opportunistic quest by aligning itself more fully with the most radical pro-Israel activists in its midst. Frenk, who took office as chancellor in January, said in a May interview with Jewish Insider that the prospect of losing federal funds “occupies me at night.” His administration has rapidly expanded the crackdown that began under Block, suspending at least 11 students over Palestine solidarity activism, placing SJP on interim suspension, and launching an “Initiative to Combat Antisemitism,” led by real estate finance professor Stuart Gabriel, to “implement” the recommendations of the university’s Task Force to Combat Antisemitism and Anti-Israeli Bias, which Gabriel chaired. Dov Waxman, a UCLA professor of Israel studies, told me that the task force report was a “problematic” document that “presented people’s perceptions or experiences of what they considered to be antisemitism as antisemitism.” He resigned from the task force rather than put his name to the draft. Another resignee, Shalom Staub, UCLA’s assistant vice provost for community engagement, told Gabriel in a September 2024 email, obtained through a public-records request, that the draft report repeatedly “conflate[d] political speech, albeit objectionable and repugnant speech, with antisemitism,” while adopting an “ahistorical, non-contextual approach” that “minimiz[ed] the context of the severe Israeli military action in Gaza post October 7.”

Yet Frenk’s maneuvers failed to keep the Trump administration at bay. Over the summer, UCLA became the first public university penalized in the government’s anti-antisemitism gambit, facing a $1.2 billion fine and a slew of other demands reflecting right-wing anti-DEI and anti-trans objectives. Negotiations between the two sides were ongoing as of press time, even after a federal judge restored virtually all of the $584 million in research funds that the Trump administration had suspended as part of its efforts. Those cuts, UC President James B. Milliken said in an August statement, did “nothing to address antisemitism”; Milliken further complained that “the extensive work that UCLA [has] taken to combat antisemitism has apparently been ignored.” But it hadn’t been ignored. On the contrary, at least one product of that “extensive work,” the antisemitism task force report, was repeatedly cited by the Department of Justice in the letter outlining its findings. Two federal grant-making agencies, the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Energy, likewise justified their suspension of funds by citing “UCLA’s own” report.

Again and again, the university’s validation of Zionist critics, far from protecting it from censure, has provided an opening for further punishment. After UCLA law student Yitzy Frankel and other plaintiffs claimed in a June 2024 lawsuit that encampment activists had made a section of campus into a “Jew Exclusion Zone,” the Trump-appointed judge in that case noted that the university “[did] not dispute this” version of events. University officials ultimately settled the case for $6.45 million. One UCLA administrator, quoted anonymously in the Los Angeles Times, conceded that the Frankel settlement—announced just hours before the Trump administration accused UCLA of civil rights violations, heralding the funding freeze—had “backfired,” inviting the federal government to pounce on the apparent admission of failure. “If you placate the bully, the bully comes back,” said legal scholar Katherine Franke, who was forced to retire from Columbia in January after being targeted with harassment and threats over her pro-Palestine advocacy.

In response to a list of detailed questions about these events, a spokesperson for UCLA said in an emailed statement that “there is no room for violence, hate or intimidation” at the university. “The events in the spring of 2024 tested the bonds that unite UCLA as a learning community and created mistrust in some corners of our campus,” the statement went on. “UCLA continues to take meaningful steps to ensure we can both maintain our commitment to free expression and make our campus a place where all Bruins feel safe, supported and able to thrive.” (The spokesperson had previously declined to make Frenk available for an interview.)

The attack of April 30th, 2024, remains an untreated wound, with the university thus far avoiding any official reckoning with its role in the most extreme night of vigilante violence endured by any Palestine solidarity encampment nationwide. The story of that night and what came after is particular to UCLA. Yet the experience of the students, treated as expendable by their own university, is vividly illustrative of the forceful opposition arrayed against the student movement as a whole. And it shows how advocates for Israel set the terms of the campus battle. “The only way UCLA really has been exceptional,” Waxman told me, “is in its exceptional failure to protect the students in its encampment from violence.”

“The only way UCLA really has been exceptional is in its exceptional failure to protect the students in its encampment from violence.”

The Fire In the Med School

Not long after October 7th, 2023, Kira Stein, an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine, started a “support group” for Jewish faculty who felt “isolated, fearful, or demoralized” by what was occurring on campus, as she later put it in an email. Stein, who is 55 and wears a blonde bob and cat-eye glasses, was affiliated with the university on a volunteer basis, seeing patients and supervising residents in a campus clinic that her mother, psychiatry professor Vivien Burt, had founded. But while Stein did not draw a salary from UCLA, she possessed an employee ID number and a university email address—and would soon make herself into a force on campus.

In the first month after the Hamas attack—with scholars and activists already warning of an unfolding genocide in Gaza as Israel laid siege to the territory, killing more than 10,000 by early November—students at UCLA’s Westwood campus were joining their peers around the country in holding rallies, walkouts, and teach-ins to advocate for divestment. A November open letter that was signed by Stein, Burt, and more than 350 other professors and affiliates decried “explicit calls for violence” at pro-Palestine rallies, citing chants featuring the word “intifada”—a term that has been associated with periods of acute resistance in Palestinian history, both violent and nonviolent—and “event advertisements featuring images of weapons/violence.” “A number of faculty members were clearly very upset” and “traumatized” by the protests, Burt, now 81 and a professor emeritus, told me recently. According to Stein, “what started as emotional support quickly evolved.”

By January, Stein’s new group, the Jewish Faculty Resilience Group (JFRG), had collected hundreds of signatures on a letter to administrators with a list of demands, including that UCLA formally adopt the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of antisemitism—which classifies broad swaths of anti-Zionist speech (including calling Israel “a racist endeavor”) as antisemitism—and that it mobilize campus police to “respond promptly to instances of violence and hate.” The group established an antisemitism tip line, organized faculty to speak at UC regents meetings, filmed student testimonials to send to congressional investigators in Washington, and put up a billboard near campus asking the public to “REPORT Anti-Jew Hate at UCLA.” Yet its aspirations went beyond local activism: In a speech at a May 2024 fundraising event at the Museum of Tolerance, Stein described her vision for a “grassroots rapid-response team and command center on every single campus.” For this, JFRG would need to “immediately” raise $1 million to counter the “terrorist organizations and foreign governments” that she claimed were financing her adversaries, like SJP, which she described as “pro-Hamas, neo-Marxist, and anarchistic.”

Like Stein and Burt, many of JFRG’s most active members are affiliated with the medical school, which, through its teaching hospitals and government research grants, generates an outsize share of revenue for the university. In the 2023 fiscal year, the most recent period for which information is available, the UCLA Medical Center accounted for about half of the university’s total $11.2 billion in revenue, an analysis of the financial data shows, far surpassing the $983 million garnered from student tuition and fees. This makes the medical school a particularly sensitive target—and gives the members of JFRG a powerful perch from which to lobby administrators. Elsewhere, too, medical faculty have been outspoken in their pro-Israel advocacy, with doctors organizing at the Columbia University Irving Medical Center and the University of Illinois College of Medicine. Yet in many ways, JFRG, which registered last year as a nonprofit and recently posted a job listing for an executive assistant to Stein, stands apart. As one UCLA medical school insider said, insisting on anonymity for fear of retaliation, “If you’re looking for the source of the fire, in terms of UCLA, it’s in the med school.”

“If you’re looking for the source of the fire, in terms of UCLA, it’s in the med school. Compared with faculty in the humanities, medical faculty are often highly paid, and even those who engage deeply in teaching or research rarely, if ever, interact with undergraduates. American medical education has traditionally “imagined itself as removed from social issues and social pressures,” said Lara Jirmanus, a family physician and clinical instructor at Harvard Medical School. But amid mainstream recognition of mounting data showing social factors like class and race to be leading health determinants, conservative-leaning doctors have sought to cast such research as “a politicized interpretation of the world that is somehow discriminatory against white people,” Jirmanus told me. In academic contexts, this view has translated into a suspicion of DEI initiatives, including on the grounds that they harm Jews. At JFRG’s Museum of Tolerance fundraiser, Burt responded to a question about “combatting antisemitism” by declaring, to applause, “We need to end DEI,” which she said casts Jews as “oppressors,” “even more so than just your average white person.”

Compared with faculty in the humanities, medical faculty are often highly paid, and even those who engage deeply in teaching or research rarely, if ever, interact with undergraduates. American medical education has traditionally “imagined itself as removed from social issues and social pressures,” said Lara Jirmanus, a family physician and clinical instructor at Harvard Medical School. But amid mainstream recognition of mounting data showing social factors like class and race to be leading health determinants, conservative-leaning doctors have sought to cast such research as “a politicized interpretation of the world that is somehow discriminatory against white people,” Jirmanus told me. In academic contexts, this view has translated into a suspicion of DEI initiatives, including on the grounds that they harm Jews. At JFRG’s Museum of Tolerance fundraiser, Burt responded to a question about “combatting antisemitism” by declaring, to applause, “We need to end DEI,” which she said casts Jews as “oppressors,” “even more so than just your average white person.”

In early April 2024, psychiatry residents Afaf Moustafa and Ragda Izar delivered a lunchtime Zoom lecture entitled “Depathologizing Resistance” to members of the medical school community. The talk took Air Force service member Aaron Bushnell’s self-immolation in protest of Israel as a provocative entry point for a broader analysis of the ways that the field of psychiatry has “pathologized actions that counter our power structures of colonization, homophobia, and white supremacy.” To Stein, a supervisor in the same department, the talk amounted to “anti-Israel and antisemitic libel” that echoed The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, as she put it in an email that evening to Chancellor Block and other senior administrators. She lambasted the administrators for their “lack of intervention after we had alerted you to the concerning nature” of the talk, even as she and her JFRG colleagues were already launching an intervention of their own. Within hours, JFRG posted a video recording of the lecture, which Stein made with a screen-recording tool, to its website, alongside screenshots of Stein’s emails to administrators, listing Moustafa and Izar’s names. The same day, Physicians Against Antisemitism—an Instagram account run anonymously by psychiatrist Katherine Hulbert that says it works “behind the scenes” with pro-Israel doxing outfits including Canary Mission, StopAntisemitism, and Jew Hate Database—published slides from the lecture, also including the two residents’ names.

This package of internal medical school material quickly found its way to right-wing media. Even after JFRG removed the video from its website—under pressure from medical school colleagues who insisted in a faculty meeting that the recording had been made illegally—an audio-only version of it, alongside the names and headshots of the residents, appeared in the Washington Free Beacon, followed by the Daily Mail. Moustafa, who is Palestinian, immediately began receiving death threats. “I was having trouble sleeping. I was having nightmares,” she told me. “I was really worried someone was going to come to my office at work, which is public information. And I got extra security at home.” More than 70 of Moustafa and Izar’s medical school peers signed a letter to Block and other administrators accusing Stein of “actively trying to silence and dox, and thereby endanger the physical and psychological safety of the only two female, Arab psychiatry resident trainees in the program.”

The department quietly suspended Stein from teaching, pending an investigation, though she remains on the volunteer faculty, Burt told me. Yet while Stein distanced herself from any doxing—“If doxing has occurred, it will be stopped,” she said during a heated exchange at the faculty meeting, a transcript of which I reviewed—the incident with the psychiatry residents was one entry in a pattern of “organized repression” of voices critical of Israel by “a small number of students and faculty” in partnership with “non-university actors,” according to the UCLA Task Force on Anti-Palestinian, Anti-Arab, and Anti-Muslim Racism in a January report on the medical school. The task force, co-chaired by two experts on race and racial violence and convened at the same time as the task force on antisemitism, described multiple instances of discriminatory abuse directed against Palestinians and their supporters of color. (In the month following the report, a Black UCLA medical student was doxed by Jew Hate Database; the post included details about her scholarship known only to a small circle at the medical school.)

Even with Stein under fire, JFRG continued to establish itself as a player in campus politics. Eight days after the “Depathologizing Resistance” lecture, it organized a group of around 25 faculty members to attend a UC Board of Regents meeting, marching from the medical center with yellow hostage ribbons pinned to their chests. They were joined by an influential outsider, Rabbi Noah Farkas, president and CEO of the Jewish Federation of Los Angeles, which is a major funder of the UCLA Hillel. “I want to say on behalf of the Jewish community that you, UCLA, are embedded in a larger city, the largest Jewish community on the West Coast . . . and we are watching you,” Farkas said when it was his turn at the microphone. “We will organize against you.”

As Trump has intensified his assault on higher education, JFRG leaders have capitalized on the opportunity, giving media interviews on “the crisis Jewish students and faculty are facing” and promoting their far-reaching demands as “the path forward.” In April of this year, two UC regents—influential Hollywood superagent Jonathan “Jay” Sures and consulting firm CEO Richard Leib—met with leaders of JFRG in a private conference room on UCLA’s campus, Burt told me. The regents, who had requested the meeting, were “obviously moved by the many things we had told them” in public-comment forums, said Burt; they saw the federal government withholding funds from Columbia and wanted to prevent something similar from occurring at UCLA. In response, JFRG created “a comprehensive, faculty-driven road map for addressing antisemitism (including anti-Zionism)” that it shared with the entire board of regents, Chancellor Frenk, and Gabriel, the antisemitism task force chair. The document recommends that the UC system adopt the IHRA definition, implement mandatory trainings “taught by vetted third-party experts aligned with the IHRA definition,” and “immediately remove antisemitic content in the medical curriculum,” among other points. “The folks affiliated with JFRG have the administration’s ear instantly,” Hannah Appel, an anthropology professor and associate faculty director of the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy, told me, noting that Frenk “routinely” repeats JFRG talking points.

“The folks affiliated with JFRG have the administration’s ear instantly.”

On campus, JFRG’s reactionary Zionist movement continues to get results: In the spring, administrators moved to end the medical school’s Structural Racism and Health Equity (SRHE) course, which required first-year medical students to grapple with how social inequities affect patient health—and which had been a favorite target for JFRG members and their right-wing allies off campus, including pundit Ben Shapiro and Do No Harm, an anti-DEI medical advocacy group that sued the UCLA medical school in May, alleging “illegal racial discrimination” that harmed white and Asian applicants. After pausing the SRHE course for a curriculum review, the school laid off the course’s tutors at the end of June, citing the “current curtailment of federal grants and funding,” according to an email sent on June 13th, weeks before any federal funding to UCLA had actually been suspended. When I asked Burt, in our September interview, about JFRG’s policing of academic material, she insisted that limits had to be placed on “political indoctrination” in classroom settings. She was pleased with the winding down of SRHE. “Whatever is being done to lessen antisemitism, we’re in favor of.”

The “Don’t Fuck With Us” Jew

On a Monday in late April 2024, Eli Tsives approached the southernmost entrance of the Royce Quad encampment. Now in its fifth day—having drawn hundreds to its discussions and teach-ins, and to the collective act of disruption it represented—the encampment had swelled beyond the quad to a nearby paved walkway. Tsives, then in the spring of his freshman year, was known to the activists as the student provocateur who’d shown up on the encampment’s very first day wearing an Israel Defense Forces t-shirt and holding an Israeli flag, and who’d gone on to post a video to his Instagram page of a confrontation with student safety marshals (“Let’s get a nice look at their faces. You can kiss your jobs goodbye,” he’d told them). Now, a friend filmed Tsives, a large Star of David dangling from his neck, as he demanded entry. The students at the steel barricades, in medical masks and keffiyehs, moved to form a wall with their bodies. By this point, experienced activists in the encampment had created a list of Zionist agitators from on and off campus who, for safety reasons, were not allowed in, according to a student organizer, Ethan, who asked that I not use his last name. These included “the undergrads who aren’t much of a threat—they’re just annoying—and the adults, who are there to get violent,” he said. Tsives was in the former category. “Everybody, look at this, look at this,” Tsives called out to onlookers off camera, giving the impression of a crowd. “I’m a UCLA student. I deserve to go here. We pay tuition. This is our school. And they’re not letting me walk in. My class is over there. I want to use that entrance,” he said, pointing past the activists toward Kaplan Hall. “We’re not engaging with agitators,” one of the students replied.

The son of two Soviet Jews who emigrated to the US in their youth, Tsives grew up south of San Francisco, playing water polo and acting in school plays. His family wasn’t particularly religious, but Tsives’s mother, now a tech executive, often spoke about Israel as an insurance policy. “She always told us: ‘If bad things happen, we’re going to Israel,’ ” Tsives said. When he was 13 and the family was living in Shanghai for his mother’s work, a science teacher at Tsives’s international school “said something along the lines of ‘The current state of Israel should not exist because of what they do.’ And I was very confused,” he told me. “My mother sat me down and grilled me on Israel education. That was pretty much the spark that lit the fire in me becoming an activist.” He arrived at UCLA just weeks before October 7th, fresh from his StandWithUs internship. When pro-Palestine protests broke out that fall—which Tsives viewed as “blatant antisemitism happening on my campus, right in front of me”—he felt galvanized. “Not a lot of things were being done about it,” he recalled. “I said, ‘If no one’s gonna do it, I’m gonna do it.’” He identifies specifically as a Russian Jew, not just an American one—a “chutzpah-driven, loud, don’t-fuck-with-us Jew.” Tsives told me, “When people hate my people, my natural instinct is to be louder and prouder of who I am.”

A theater major at the time of the encampment, Tsives said that the class he was trying to get to on that Monday in late April was Introduction to Lighting Design, which met in Kaplan Hall (he has since switched his major to political science, in part because of the “absurd amount of antisemitism and anti-Zionism happening in the School of Theater, Film and Television,” he told me). But Kaplan Hall has six main entrances; the encampment was blocking only two, on the building’s western side. The closest unobstructed entrance was roughly a 45-second walk south from the spot where Tsives starred in his one-minute video. Waxman, the Israel studies professor—who was a critic of the encampment at the time, posting on X the week it appeared that “groups like SJP” were “exploiting the sympathy that many students rightly feel for the suffering of Palestinians”—told me that students “could simply walk around the encampment.” Though it was “in a central part of our campus,” he said, “it didn’t block any building. The idea that Jewish students couldn’t enter UCLA, or couldn’t go to class, is just misrepresentation.” When I asked Tsives why it was important to him to use that particular entrance with other entrances nearby, he said, “There’s no reason why masked protesters who are harassing Jewish students should tell me to walk around the school just because I’m a Jew.”

Though the encampment was “in a central part of our campus,” Waxman said, “it didn’t block any building. The idea that Jewish students couldn’t enter UCLA, or couldn’t go to class, is just misrepresentation.”

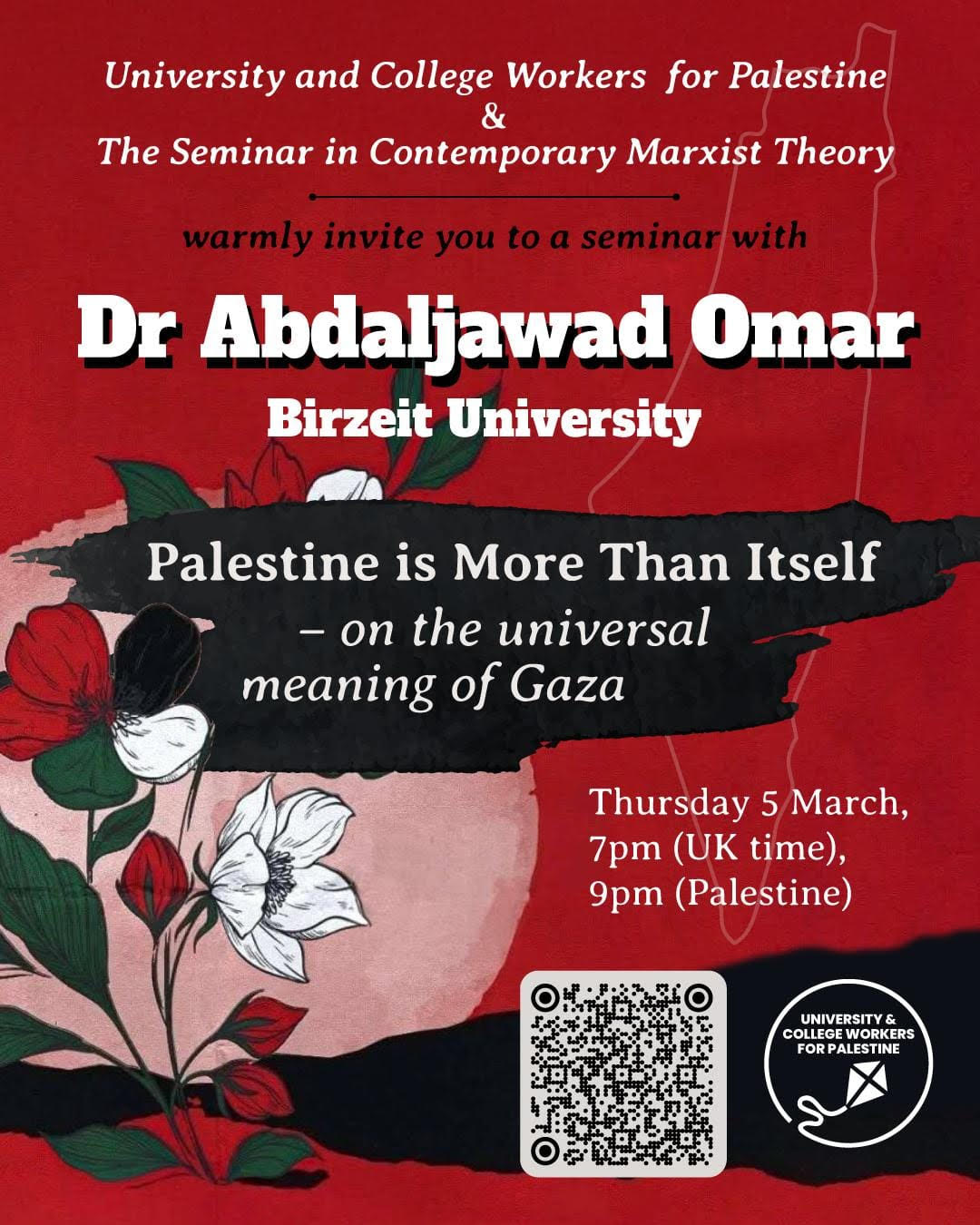

Eli Tsives in the April 2024 video in which he claimed he was being blocked from getting to class.

Tsives’s performance, with his insistence that the activists were promoting “aggression” and “hate,” entered the cultural bloodstream. Promoted by influential right-wing accounts, the video spread like wildfire through Jewish networks and family group chats, racking up millions of views across Instagram and X, and was soon featured on Fox & Friends. But its influence extended beyond the Jewish echo chamber and the culture-warring right, making its way to CNN’s Inside Politics, where a stone-faced Dana Bash followed the clip with sensationalized commentary: “What you just saw is 2024 in Los Angeles, hearkening back to the 1930s in Europe. And I do not say that lightly.”

The university swiftly endorsed Tsives’s narrative. Flooded with complaints from parents, alumni, and politicians, Chancellor Block, in his first university-wide email about the encampment since its creation, declared that “students on their way to class have been physically blocked from accessing parts of the campus,” putting Jewish students “in a state of anxiety and fear.” By that point, journalists and other observers had documented numerous instances of harassment directed at students in the encampment, including physical shoving and shouted threats of violence, by a loose confederation of Persian Jews, Israeli Americans, and other off-campus locals. “It was rare to have a moment where at least one random middle-aged Zionist wasn’t trying to get in,” Ethan told me. But Block’s official email, which condemned “instances of violence completely at odds with our values as an institution,” declined to say who was committing the violence. Graeme Blair, a political science professor who serves as one of the spokespeople for the campus chapter of Faculty for Justice in Palestine, told me that he believes Block’s equivocating statement, which validated and amplified incendiary claims, was “one of the key factors that led to the escalation of violence” in the April 30th mob attack. “They’re stopping students from going to their classes,” one of the attackers told local news channel Fox 11 that night. “We’re here to stop them from doing what they’re doing.”

There are a number of Eli Tsiveses nationwide—Zionist students like Shabbos Kestenbaum at Harvard, Bella Ingber at New York University, and Lishi Baker and Eden Yadegar at Columbia—who, in one way or another, have successfully bent their schools toward their version of reality. Many of these students have been the faces, and beneficiaries, of lawsuits against their universities. Kestenbaum sued Harvard over “rampant anti-Jewish hatred and harassment” on campus; his co-plaintiffs settled in January, winning concessions including undisclosed “monetary terms” and a pledge that Harvard would adopt the IHRA definition of antisemitism, while Kestenbaum held out for a separate settlement in May. Ingber also received an undisclosed settlement from NYU over assault claims that, though challenged by security footage, separately resulted in another student being charged with a hate crime (a grand jury could not be persuaded to indict the student, and the charges were dropped). At schools across the country, “the students who have actually caused harm are the ones winning thousands of dollars in university settlements,” Noura Erakat, the prominent Palestinian American human rights attorney and Rutgers professor, told me. “Their grievance aligns with power’s aspiration for expansion.”

Beyond the financial rewards, these students’ political activism has launched them into the world of influence. The path they’re on was charted by the famed pundit Bari Weiss, who first rose to prominence as a campus crusader at Columbia in the early 2000s and whose staunchly Zionist outlet, The Free Press, was recently acquired by CBS. Few among the latter-day Weisses can rival Tsives’s following on social media, which numbers more than 50,000 on Instagram, but Kestenbaum provides another study in mainstream sway. He broke through on the stage of the 2024 Republican National Convention, where, in his kippah and hostage dog tag, he sold himself as a former Bernie Sanders supporter disgusted with the Democratic Party’s abandonment of the fight against antisemitism. In May, he was the subject of a sympathetic New York Times profile, “The Jewish Student Who Took On Harvard,” which portrayed him as the glad-handing David to Harvard’s Goliath. Tsives first met Kestenbaum, whom he described as a “good friend,” on his first trip to Israel, at 16, through the National Conference of Synagogue Youth, where Kestenbaum, who is six years older, was an assistant bus director. “He’s been part of my journey,” Tsives said of Kestenbaum, “I’ve been part of his.” This year, the two were promoted as “visionaries and advocates” on a slate of candidates, which also included Ingber, in the World Zionist Congress elections. But they have their sights on American politics: Kestenbaum told Jewish Insider that, at the encouragement of “New Yorkers from a broad ideological spectrum,” he was considering a run for retiring Democratic representative Jerry Nadler’s House seat. When Tsives met the Israeli celebrity and activist Noa Tishby at a May 2024 event, she anointed him the future “first Jewish president” of the US. “I will be,” Tsives told me. “That is the end goal.”

Bean-Bag Rounds and Flash-bang Grenades

It was just before midnight on April 30th, 2024, when UCLA police chief John Thomas arrived on campus. By that time, attackers had begun tearing down the encampment’s steel barricades and shooting fireworks at the activists inside. One of Thomas’s lieutenants had requested help from the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) to quell the escalating violence; the university would soon call in the California Highway Patrol (CHP) as well. But the 19 officers assembled there upon Thomas’s arrival were hanging back. An LAPD lieutenant informed him that the force was too small and that they had to wait, Thomas told the Los Angeles Times. (He was later reassigned and left the UCLA police department in December.) “No one from UCLA PD took command of the scene,” according to a UC-commissioned report completed in November 2024 by the consulting firm 21st Century Policing Solutions; officials from outside police agencies got the impression that “no one was in charge.” That week, administrators had engaged in a “chaotic” decision-making process “without clarity on who maintained final decision-making authority,” according to the report. This resulted in “institutional paralysis” and “an inability to effectively respond and protect students from violence.” On the night of the attack, with students being bloodied, the police did nothing. In one instance, past 2 am, when assailants rushed the encampment and slammed a plank of wood into someone’s head, police officers some 200 feet away stood still, according to an analysis of video by The Washington Post.

When assailants slammed a plank of wood into someone’s head, police officers some 200 feet away stood still.

The attackers viewed the student activists as “outsiders” who had “violated” the firmly rooted Persian Jewish community—as Sean Tabibian, a real estate developer on the scene that night, told me—and they assumed that the police would take their side. Tsives, who was there to observe at the behest of a Fox & Friends booker, said on the show that the attackers told him that “the main reason they were doing this was to attract police [to] finally go inside the encampment and start making arrests.”

University officials have claimed in court documents that they were already planning to remove the encampment when it was attacked. Those plans quickly translated into action as the sun rose on May 1st. In a meeting that afternoon attended by Chancellor Block, UC President Michael V. Drake, and LA Mayor Karen Bass, the UCPD and outside police agencies sketched out a plan for ending the encampment: The CHP—which has authority over state property, including university campuses—would dismantle the barricades and arrest protesters, the LAPD would protect the CHP, and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department would bus arrestees downtown for booking, according to an after-action report by the LAPD. (Such “mutual aid” requests by campus police that spring, along with private security, ultimately cost UCLA $10 million, the most of any UC campus.)

As sheriff’s deputies pulled up to Wilson Plaza, rumors of a police sweep spread across campus. The student activists—exhausted from the attack the night before—reinforced the encampment perimeter with wooden pallets and collected hard hats, goggles, umbrellas, and other protective gear. Starting just before 6 pm, a dispersal order played over loudspeakers declaring the encampment “an unlawful assembly” and telling the students to leave or risk arrest. Many people did leave over the ensuing hours, but hundreds remained, keeping up their call-and-response chants as police and news helicopters thundered overhead, and as large formations of officers marched outside the encampment walls. (Nearly 600 officers from the LAPD alone responded to the UCLA protests between April 30th and May 3rd, according to the city controller.) “That was the day that it hit: UCLA has changed forever,” Dylan Kupsh, the SJP activist, told me. “It marked a turning point in the militarization of campus.”

The raid began in the predawn hours, when armored CHP officers fired 12-gauge shotguns loaded with bean-bag rounds, as well as grenade launchers with sponge rounds designed for “pain compliance,” at the students, discharging a total of 57 projectiles, according to the CHP’s use of force report. An investigation by the nonprofit newsroom CalMatters found at least 25 instances in which the officers “appeared to aim their weapons at the eye level of protesters or fired them into crowds,” in apparent violation of training guidelines and state law. (The CHP, in its one-page report, said that the officers were defending themselves against frozen water bottles and other thrown items and that they did not fire “indiscriminately in the crowd of protesters.”) One student, Kira Layton, was shot in her right hand. She needed surgery to install screws in her metacarpal bones and intensive physical therapy. “It stopped my life completely,” she said, her voice unsteady under the weight of the memory, at a press conference on campus this May to announce a lawsuit, alongside other plaintiffs, against the city of Los Angeles and the state of California. A reddish mark from the injury was still visible, 12 months later, on the hand clutching the microphone. “I couldn’t work. I couldn’t go to school. I had to move out of the apartment I was living in to stay with my mom. I couldn’t sleep.” Returning to campus in the fall, she experienced panic attacks and started failing her classes “for the first time in my life.” In the course of arresting 209 people the night of the sweep, the police dealt emergency-level injuries to at least 15, including head trauma from fired projectiles and burns from flash-bang grenades. The encampment was reduced to a heap of smashed and overturned tents on the matted lawn.

“That was the day that it hit: UCLA has changed forever. It marked a turning point in the militarization of campus.”

In an administrative shake-up three days later, Block shifted command of the campus police to a new Office of Campus Safety, whose inaugural head, Rick Braziel, a former Sacramento police chief still living in the state capital, reported directly to him (while earning $52,000 a month for the short-term role). Faculty activists privately referred to this new office as UCLA’s version of the Department of Homeland Security. The university had consolidated power in the hands of the police, and the effects were immediately apparent: On June 10th, 2024, after a long afternoon of protests that included attempts to read the names of Palestinian dead in different places on campus, UCPD officers kettled students in a narrow passage between two hedges outside the law school, forcing them back, videos show, into a line of LAPD officers. Jakob Johnson, a history major then in the final days of his senior year—and now a plaintiff in the omnibus lawsuit against university officials—saw a UCPD officer aim a grenade launcher at his chest from less than ten feet away. The sponge-tipped bullet “completely knocked the air out of my lungs,” Johnson told me. At the emergency room, after coughing up blood, he was treated for contusions on his lungs and heart. Johnson is a dedicated runner; for months afterward, the injury significantly limited his aerobic capacity. “It just felt like my lungs would stop functioning” beyond a certain point, he said. The recovery also included a period of severe depression. Having planned to matriculate to law school at the University of California, Berkeley, Johnson withdrew two weeks before the start of classes that fall. “For my own university, where I’ve come into myself in so many ways, and which has given me the education that put me out there in the first place—for that university to shoot me just shattered so much,” Johnson said, when we met on UCLA’s campus in May. “Any faith I had in the institution was lost.”

“Parents are sending their kids to schools with the assumption that the school won’t make intentional choices to harm them,” said Ricci Sergienko, a civil rights lawyer representing Layton and other plaintiffs in the lawsuit against the state and city governments. “When you call in the police, you’re ensuring violence against young people.” The increased reliance on militarized police to suppress student protests is itself an alarming sign of UCLA’s priorities, his co-counsel Colleen Flynn told me; the administration is “willing to sacrifice the safety and physical well-being of their students to keep the money flowing in.”

Lawfare Finds “UCLA in Full Retreat”

At 12:13 am the night of the mob attack, as the violence raged, JFRG posted on X that it “unequivocally condemns the clashes and riots on our campus.” Mainstream Jewish groups likewise moved quickly to express their disapproval of “the abhorrent actions of a few counterprotesters,” as LA’s Jewish Federation put it. Yet even then, a counternarrative was already forming—virtually from one paragraph to the next, in the Federation’s statement—that shifted the focus to the “illegal encampment” and the question of “Jewish safety.” In her speech at the Museum of Tolerance event weeks later, JFRG’s Stein asked the audience to imagine “if you [had] to show a wristband . . . to be allowed free access to public property.”

The wristbands had become a symbol, among campus Zionists, of perceived anti-Jewish discrimination. It was true that activists had used a wristband system to speed re-entry to the encampment. The requirement for getting one, organizers told me, was to agree to a set of community guidelines, including “I will not use cigarettes, drugs, or alcohol,” “I will respect everyone’s preferred names, gender pronouns, and expressed identities,” and “I will not wield a weapon or act violently.” The guidelines make no reference to Israel or Zionism. At the same time, in at least one case caught on video, an activist asked someone seeking entry if they were a Zionist—which, for the activists, served to gauge hostility toward their project. “It was never ‘encampment policy’ to ask people if they were Zionist or not,” one Jewish Voice for Peace organizer told me, while acknowledging that, in part because of “constantly shifting circumstances,” with activists “cycling in and out of roles,” the question was sometimes asked.

“It was never ‘encampment policy’ to ask people if they were Zionist or not,” one JVP organizer told me, while acknowledging that, in part because of “constantly shifting circumstances,” with activists “cycling in and out of roles,” the question was sometimes asked.

In June, Yitzy Frankel, then a UCLA law student, filed a lawsuit alongside other plaintiffs accusing UCLA and UC officials of failing to protect Jewish students and faculty, and specifically claiming that pro-Palestine activists in the encampment were excluding Jews. It was not that protesters had physically blocked Frankel from activities on campus; instead, he claimed that the “knowledge that he could not go through the encampment without violating his faith by disavowing Israel” forced him to change his routine. Describing the encampment as a “Jew Exclusion Zone,” the complaint pointed to the wristband system, which, it said, involved swearing fealty “to the activists’ views.”

Representing Frankel were two firms known for their conservative activism: the Washington, DC, firm Becket Fund for Religious Liberty—which represented the craft store Hobby Lobby in its successful Supreme Court effort to deny birth-control coverage to its employees—and Clement & Murphy, led by Paul Clement, who served as solicitor general under George W. Bush. The lawyers pursued a careful legal strategy: As an Orthodox Jew, the complaint read, Frankel “believes, as a matter of his religious faith, that he must support Israel.” Legally, Frankel’s argument was “a little bit narrower than ‘to be a Jew is to be a Zionist,’ ” said Noah Zatz, a UCLA law school professor. “It’s ‘For me, to be a Jew is to be a Zionist,’ in a religious sense. It actually lowers the burden, because they don’t have to get into an argument about the intrinsic nature of Judaism.”

In its legal defense, the university did not dispute the idea that the encampment excluded Jews; rather, it argued that the activists’ “antisemitic conduct” was “not perpetrated by UCLA.” The result was that the “Jew Exclusion Zone” narrative “risk[ed] becoming the official record of the Palestine Solidarity Encampment,” wrote Thomas Harvey, a lawyer representing Jewish pro-Palestine activists and others, in an unsuccessful motion to intervene in the case. On August 13th, 2024, two months after the lawsuit was filed, Judge Mark C. Scarsi issued a preliminary injunction that prohibited UCLA officials from “offering any ordinarily available programs, activities, or campus areas” that “are not fully and equally accessible to Jewish students,” and specified the protection of Jewish students’ “religious beliefs concerning the Jewish state of Israel.” (Harvey, in his motion, warned that this conflation of “political perspective” and “protected religious belief” would “infringe on the free speech rights and religious freedom of anti-Zionist Jews or anyone else who criticized Zionism as a political project.”) UCLA appealed the injunction, stating through a spokesperson that the ruling “would improperly hamstring our ability to respond to events on the ground.” An injunction, the university had argued in a filing, would effectively allow “the Court to take the reins and manage UCLA’s response to protest activity on campus, down to ordering when and where law enforcement should be deployed.” Yet the appeal immediately drew a howl of protest from JFRG. “REALLY, UCLA?” the group said in an X post, plastering the words in red lettering on an image of a court document. “Why is UCLA appealing a ruling that bars anti-Jewish exclusion on campus!?” Eight days later, the university backed down, withdrawing the appeal and accepting the injunction. Mark Rienzi, the president and CEO of the Becket Fund, said in a statement, “We’re glad to see UCLA in full retreat.”

Universities across the country have similarly retreated in the face of “nuisance suits” that “have no legal basis,” according to Franke, the retired Columbia law professor. These legal efforts typically rely on Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which protects students from discrimination based on “race, color, or national origin”—and whose use in antisemitism cases dates to a novel interpretation of the law promoted by Kenneth Marcus, who led the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights in the post-9/11 era. Since October 7th, 2023, pro-Israel advocates across the country have filed 26 lawsuits, including the Frankel case, against colleges and universities alleging antisemitism under Title VI, compared with just two such cases in the years prior, according to data compiled by the Middle East Studies Association’s Academic Freedom Initiative. (This tally does not include the roughly 100 Title VI antisemitism investigations opened by the federal government in the last two years.) Of the 28 total suits, nine have had their Title VI claims dismissed at an early stage of the proceeding, with judges sometimes ruling that the alleged antisemitism actually counted as political speech protected by the First Amendment. One reason judges have not dismissed more of these claims, according to Radhika Sainath, a senior managing attorney at Palestine Legal, is that universities, under political pressure, are generally “not making all the arguments they should.” Nine cases have resulted in settlements. Franke called it “appalling” that universities “are settling the suits and paying out large sums of money.” She said, “The law is being used in a range of ways to extract funds from our institutions through private litigation that parallels what the government is doing in pulling public funds.”

“We’re glad to see UCLA in full retreat.”

The University of California settled the Frankel lawsuit in July. In addition to making Judge Scarsi’s injunction “permanent” for 15 years or more, the deal required UC to contribute $320,000 to UCLA’s new Initiative to Combat Antisemitism—charged with implementing the task force recommendations—and $2.3 million to a list of Jewish and Zionist organizations including the ADL. UC also agreed to pay $3.6 million to the lawyers who brought the case and $50,000 apiece to Frankel and the three other plaintiffs. (In response, Shabbos Kestenbaum tweeted a now-deleted message of congratulations “to my friend Yitzy and the other plaintiffs at UCLA for this historic win,” adding, “I encourage ALL Americans: hold your universities accountable! DM me if I can be of help.”)

At UCLA, legal challenges to the pro-Palestine movement have played out on an individual scale, too. In late May, Dylan Kupsh found himself in a downtown LA courtroom, looking the part of a slightly bewildered computer science grad student in a rumpled white dress shirt and black slacks. At the table to his left were lawyers for United Talent Agency vice chairman Jay Sures, who, as a UC regent, helped oversee university investments, and who had been a vocal opponent of the student movement. Sures was seeking a restraining order against the 26-year-old Kupsh, whom he had described in a sworn declaration, citing information from the UCPD, as “the ring leader” of “a pro-Palestinian mob”—a reference to the group of students who had protested outside Sures’s home in a leafy Brentwood cul-de-sac on a February morning, leaving handprints in red paint on his garage. (Kupsh told me that SJP does not have an individual leader; he believes he was targeted because, as a frequent police liaison at protests, he was known to the UCPD.)

In court, Sures’s lawyers claimed that their client, who is Jewish, was a victim of antisemitism, even postulating that the pigs depicted on a banner held by the students were wearing yarmulkes. Judge Kimberly Repecka wasn’t buying it; the pigs’ hats were clearly police hats. “They look very much like the cartoon images from the ’60s and ’70s of law enforcement officers that are specifically meant to mock them as pigs,” she said. She granted Kupsh an anti-SLAPP motion under the California law that protects individuals targeted for exercising their free-speech rights on a public issue. Running through a list of the evidence, the judge repeatedly found that particular allegations made by Sures, including that he was targeted as “a prominent member of the Jewish community,” reflected not what had actually occurred, but rather “Mr. Sures’s state of mind.”

Yet only a week after Sures’s case fell flat, UCLA informed Kupsh that he had been placed on interim suspension and immediately barred from campus. This punishment, according to a letter Kupsh received from the Office of Student Conduct, resulted from an accumulation of five outstanding student-conduct cases he had collected for his activism over the past year; among the accusations in those cases was that Kupsh had been “repeatedly asking questions” of university officials at a Nakba Day protest “in an apparent attempt to distract” them. The office had determined that there was “reasonable cause to believe” that Kupsh’s presence on campus would “lead to other disruptive activity.” (Kupsh was one of three students who received similar letters that day.) Kupsh—now entering the fifth year of his PhD program—may lose his employment as a graduate-student instructor or even be forced to withdraw entirely. His fate will depend on Zoom-based student-conduct hearings like the one I attended across two sessions in June and July, where a panel of two students and one university staff member heard allegations that Kupsh “participated in setting up an unauthorized encampment . . . after having been warned and ordered by University officials to disperse.”

“There’s been a full year of investigation into this case, one that’s been pretty stressful,” Kupsh said in a prepared statement in the July session, sometimes pausing to draw a steadying breath. Ultimately, after hearing testimony from a dozen witnesses, including students and professors whom Kupsh had rallied to his defense, the panel found for Kupsh, citing “insufficient information.” If he wants to remain a student at UCLA, Kupsh must successfully repeat this exercise four more times.

“Vindication” for JFRG

In August, with the Trump administration demanding $1.2 billion from UCLA to settle claims over alleged antisemitism, David Myers, a prominent professor of Jewish history and director of the UCLA Initiative to Study Hate, joined other faculty organizers in collecting more than 360 signatures for an open letter, “Jews in Defense of UC,” intended to show the university that campus Jews and alumni representing “a diverse range of approaches and opinions about how to define and combat antisemitism” stood united against the Trump administration’s efforts. But Trump has crudely written off the many Jews who dissent from his right-wing vision, while UC administrators have offered scant acknowledgment of the intra-Jewish ideological diversity that the letter reflects.