18 February 2026

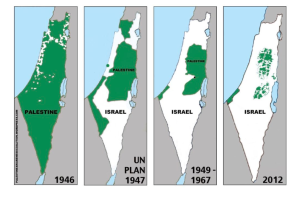

Israel has denied access to Gaza for years, but until recently it was possible to visit the Occupied West Bank and, for those prepared to do so, accompany Palestinian school children and farmers being harassed by Jewish settler terrorists.Those days have passed, it seems. The Israeli immigration authorities are increasingly denying visas to would-be visitors concerned for the welfare of Palestinians in the OPT, and IDF soldiers and police, using facial recognition technology, are identifying “troublemakers” who have reached the OPT and ordering them out of the country. The aim? Israel won’t admit it, but presumably it’s to minimise witnesses to the second Nakba and its accompanying violence. Here is a disturbing report from +972

No explanation, no appeal: Israel revoking entry authorization of foreign activists

The government is exploiting the visa-free travel system to clamp down on activists supporting vulnerable Palestinian communities in the West Bank.

By Liam Syed February 18, 2026

When Katya* applied for an Electronic Travel Authorization (ETA) to return to the occupied West Bank in June 2024, she did not expect Israel to approve it. Twenty years earlier, the long-time Palestinian rights activist had been deported following her arrest by Israeli forces in the Palestinian village of Bil’in, during one of the weekly demonstrations against the construction of the separation wall.

Katya, a Jewish American who described her experience with the Israeli immigration system in 2005 as “pseudo-legal and Kafkaesque” (it included five weeks in jail waiting for an appeal hearing, which was ultimately set for the day after her visa expired), assumed she would never be allowed to return. Yet when she applied for the ETA — now required of all travelers from visa-exempt countries seeking to enter Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories — her application was granted.

On Nov. 11, 2024, Katya entered the country and returned to the West Bank, where she was immediately struck by the vast expansion of Jewish settlements during the intervening two decades. Three days later, during her first full day of protective presence activism (aiming to document and deter settler violence) in the village of Qusra, soldiers on a routine patrol stopped her and photographed her passport. A week after, she and the three activists who were with her that day received identical emails: “Due to a change of circumstances in your case, the ETA-IL approval for application number [redacted] has been revoked.”

The message offered no explanation for the decision, nor any timeline or avenue for appeal. It meant that once Katya exhausted the 90-day limit of her tourist stay, she would be unable to return for at least two years. Others present who had entered Israel before ETAs became mandatory faced no consequences.

For Katya, the contrast between her ETA revocation and her deportation process 20 years earlier was striking. In 2005, there had at least been a theatrical pretence of due process — hearings, judges, and motions — even if the outcome was largely predetermined. The ETA revocation dispensed with even that performance, reducing the whole process to a single email. The bureaucratic machinery that Katya originally encountered had been streamlined into something more efficient and far more difficult to challenge.

The practice of revoking ETAs is the latest addition to a growing arsenal of tools deployed by Israeli authorities to remove international left-wing activists from the occupied West Bank. It comes after National Security Minister Itamar Ben Gvir launched a self-described “task force for dealing with anarchists” in April 2024 — a police unit dedicated to detaining, deporting, and gathering intelligence on activists doing protective presence in Palestinian communities.

The state has done little to disguise who this strategy targets. In September 2025, British journalist Owen Jones — a vocal critic of Israeli military conduct — had his ETA revoked just two days after arriving for a visit to Jerusalem and the West Bank with the Palestinian Christian charity Sabeel Kairos.

“On the way back, a border official semi-angrily waved my passport in my face and said, ‘Next time you want to go to Israel, you go to the Israeli Embassy in London first, do you understand?’” Jones told +972.

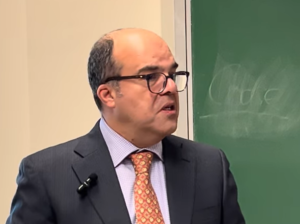

In January, French historian Vincent Lemire, who has been traveling to Israel for over two decades, received the same vague email alerting him that his ETA had been revoked. A scholar of Israel-Palestine, Lemire was the head of the French Research Center in Jerusalem from 2019 to 2023. The email came after he publicly called on France to sanction Israel over the humanitarian crisis in Gaza (he also consistently called for the release of Israeli hostages held by Hamas).

“My positions are not new, but I have never boycotted Israel,” Lemire told AFP. “I have regularly issued invitations to Israeli academics and I have been going to Israel for 25 years, so I am very surprised.” After diplomatic pressure mounted, authorities reversed the decision — an avenue far less accessible to activists without institutional support or media visibility.

Unlike deportations, which can provoke costly diplomatic and media fallout, ETA revocations are fast, quiet, and indeterminate. Through interviews with eight activists whose ETAs were revoked in the past year and a half, +972 traced how Israel is transforming the travel authorization framework into a systematic method of removing foreign activists from the West Bank and isolating Palestinian communities.

‘Palestinization’ of foreign activists

Over the past few years, electronic travel authorization systems have become a common tool for states to pre-screen visa-exempt travellers. The United States, Australia, and the UK have all implemented ETAs (or ESTAs, in U.S. parlance), and they are set to be rolled out across the Schengen Zone later this year.

Israel announced its own ETA system in May 2024 and made it mandatory for visa-free nationals starting in January 2025. Applicants must provide passport information, intended dates of travel, accommodation details, and employment information at least 72 hours before arrival and pay NIS 25 ($8). Applications are officially processed within 24 to 72 hours, but are often approved within minutes.

‘I almost thought it was a mistake’

When Nicole Erin Morse — an outspoken anti-Zionist and long-standing member of Jewish Voice for Peace — received notice on Jan. 8, 2025 that their ETA had been revoked, they were in the West Bank doing protective presence. Seeking clarification, they replied to the revocation email and received a confusing response: “Based on the circumstances of your planned arrival to the State of Israel, it has been decided to cancel the ETA-IL authorization that was granted to you.”

“‘The circumstances of my planned arrival’? I had no planned arrival,” Morse told +972. “I was already there, and then I left.”

For Morse, who is Jewish, being barred by Israeli authorities was emblematic. “This reinforced my belief that the State of Israel has nothing to do with Judaism,” they said.

Anuradha Bhagwati, a U.S. military veteran who now dedicates her work to Palestinian advocacy, received her revocation email the same week, likewise citing a “change of circumstances in your case.” “It was polite,” she told +972. “It had no tone — it didn’t accuse me of anything. I almost thought it was a mistake.”

An arbitrary mechanism of control

While Frost’s deportation proceedings made explicit that her political views were the reason for her removal, activists who receive only ETA revocations are left guessing why they were targeted, and what the terms of their new status might be.

When Chava, a Jewish-American activist doing protective presence with the Center for Jewish Non-Violence, received her revocation on Sep. 9, 2025, she contacted PIBA to find out why. What followed was a deliberately long and confusing process — one so exhausting, she said, that most activists never attempt it.

In an interview with +972, she recalled one incident during her stay when soldiers checked her documents and threatened arrest, though they ultimately did not follow through. Her passport was scanned twice, which she suspects may have triggered the revocation. But the activist beside her that day — whose passport was also scanned — has not had their ETA revoked.

The arbitrariness of cases like Linda’s and Chava’s has itself become a mechanism of control. Without knowing what triggers a revocation or how long a ban lasts, activists are left to operate in a state of constant uncertainty. When identical circumstances produce different outcomes — friends in the same location, one revoked and one not — it becomes nearly impossible to discern precedent or mount an effective appeal.

“You’re going to fear the police, you’re going to fear the military, because you might get revoked,” Berda said. “They’re pulling the rug from under their feet in terms of the privilege that foreigners have [relative to Palestinians under Israeli law].”

Troublingly, several activists said they could not identify any specific incident that might have triggered their revocation. During Chava’s last trip to Umm Al-Khair — she arrived three weeks after Awdah Hathaleen’s murder to be with the grieving community — she said she did not directly encounter soldiers or police at all. “This was the only trip where I had absolutely zero interaction with them,” she recalled.

Yet two weeks after leaving, Chava received notice that her ETA had been revoked. “It was awful and very surprising, especially because there wasn’t a clear change. I hadn’t gotten arrested,” she said. “I have friends in the exact same position as me, who lived in Masafer Yatta at the same time as me, and who still have their ETA. It’s very arbitrary.”

Like nearly all the activists interviewed, Chava said she had scrubbed her social media presence before traveling. While monitoring online activity is widely understood to form part of Israel’s intelligence apparatus, she believes her revocation is more likely tied to accumulated on-the-ground encounters with soldiers and police than to any digital footprint.

In March, +972, Local Call, and The Guardian reported that the military had begun developing AI-driven systems designed to integrate previously siloed intelligence databases on individuals in the West Bank, including activists. Chava suspects these tools played a role in her case. “Before, when police would take your ID, they didn’t really have any information about you,” she said. “Now, their systems have been linked together, and that shift happened very recently.”

She believes she may have been flagged upon entry, when her consolidated profile surfaced years-old interactions with soldiers and police. “They’re creating profiles based on proximity to Palestinians and proximity to areas with lots of activists,” she said. “They’re surveilling activists.”

‘They were with me in the hardest time’

Six of the eight activists interviewed had worked with the International Solidarity Movement — an organization that brings volunteers from around the world to the West Bank (and, until 2006, to Gaza) to provide protective presence.

For networks like ISM, ETA revocations pose a significant threat. By removing experienced activists, the system erodes institutional knowledge: how to navigate checkpoints, coordinate with Palestinian families, and document violence effectively. As a result, they are left with a rotating roster of new, inexperienced volunteers. “They don’t want witnesses,” Frost said.

Revocations also sever long-term relationships. For activists who have built years-long ties with Palestinian communities, losing access means being cut off from people they consider family.

Hanady Hathaleen — the widow of Awdah and mother of their three young sons — has had to say goodbye, potentially for good, to several international activists who supported her after Awdah’s killing. Before their ETAs were revoked, June, Chava, and Bhagwati had spent extended periods living in Umm Al-Khair, supporting Hathaleen and helping care for her children.

“They were holding my hand through the first month after Awdah’s murder,” Hathaleen said. “They were with me in the hardest time.”

For Hathaleen, the revocations represent another layer of control over her life. “She was really close to me and my boys, and now she will be far away from my boys,” she said of June. “And Anuradha was like a big sister to me.”

Nora, an activist whose ETA was revoked in September, sees the policy as part of a broader effort to isolate Palestinian communities. “When I will be able to go back, who will be left and who will still be there?” she asked, referring to the constant threat of displacement in the West Bank.

“The indecency of banning someone from connecting with a loved one is the worst thing about all of this,” Bhagwati said. Because of her revocation, she fears she may be unable to attend the funerals of elders she describes as closer than blood relatives.

June maintains daily contact with the Palestinian family she lived with, frequently video-calling the children. The boy she was closest to repeatedly asks when she is coming back. She tells him it won’t be soon — perhaps a year at the earliest, perhaps never.

PIBA and the Interior Ministry did not respond to requests for comment.

*Some interviewees are identified by first name only or with a pseudonym to protect their identity.

Charlotte Ritz-Jack contributed reporting.

Liam Syed is an independent journalist and photographer based in Paris. His work focuses on conflict, human rights, and activism.