31 October 2025

Sabri Jiryis’ masterful history of the Zionist movement, which for years was available only in Arabic, has now been published in English translation. As he explains in this interview for Mondoweiss, the record of injustice inflicted upon the Palestinians, and not least those in Israel, is essential for a final reckoning.

Palestinian scholar who wrote iconic book on Zionism reflects on the Gaza genocide and our duty to history

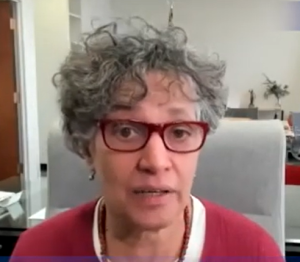

Mondoweiss speaks to celebrated Palestinian scholar Sabri Jiryis about his life, Zionism, the genocide in Gaza, and the judgements of history.

By Louis Allday October 30, 2025

Originally published in Arabic in two volumes in 1977 and 1986, the esteemed Palestinian scholar Sabri Jiryis’ Arabic-language History of Zionism, is now available for the first time in English as The Foundations of Zionism. Released on October 7, 2025, with a newly written conclusion, this edition was translated by the author’s daughter, Fida Jiryis, and published by the Liberated Texts/Ebb Books collaborative series, following the release of On Zionist Literature by Ghassan Kanafani in 2022.

Here, the editor of this series, Louis Allday, speaks to Jiryis about his life’s work and struggles, the genocidal destruction in Gaza, the importance of historical research, his seminal 1966 book The Arabs in Israel, the situation of the so-called 48 Palestinians then and now, as well as the fascinating backstory of how his study of Zionism began and what his hopes are for the new English language version.

Louis Allday: Thank you for agreeing to do this interview, Sabri. It is much appreciated.

A recent article published by the Institute for Palestine Studies about the destruction of printing and publishing houses in Gaza immediately made me think of the Palestine Research Center in Beirut and the attacks it faced during Israel’s onslaught against Lebanon in 1982-83. For those unfamiliar with the Center, could you please explain briefly what it was, how you came to run it, and its central role in cultural resistance to Zionism at the time? What parallels do you see between then and now?

Sabri Jiryis: Israel has not only destroyed printing and publishing houses in Gaza, but almost everything, including universities, schools, libraries, hospitals, clinics and all aspects of civilian infrastructure. I think this is part of the hostility of the Zionist movement towards Palestinian culture, in particular, and Arab culture, in general.

The Palestine Research Center was established by the PLO in 1965, in Beirut, as the cultural arm of the organization, and to research and document all matters relating to Palestine and Israel, especially after the wholesale destruction of Palestinian culture during the Nakba.

I was born in 1938 in the Galilee, in what was then Mandatory Palestine. My village was occupied in 1948, and I became a citizen of the new Israeli state. I grew up to study law and became a political activist, as a result of which I was forced to leave the country in 1970. I worked for a few years at the Institute for Palestine Studies in Beirut, then joined the Palestine Research Center and eventually came to direct it. At the time, the Center was a thriving hub of research and publication. It produced the monthly, Arabic-language Shu’un Filastiniyya (Palestine Affairs) and published dozens of books and periodicals on the Palestine question and on Israel, compiling whatever it could of books and documents into a library — which was seized by Israel during its invasion of Beirut in September 1982. Five months later, a car bomb planted by pro-Israeli agents destroyed the Center and killed several of its employees, including my wife, Hanneh, who had worked with me as a researcher of Israeli affairs. Some weeks later, I was arrested by the Lebanese authorities and expelled from Lebanon, with my two young children.

The loss of the Center was a huge, bitter blow to Palestinian culture. In the wake of this, the PLO made a decision to move its cultural institutions to Cyprus, and my small family moved there. The Center was reopened, on a smaller scale, and a number of its employees also came to join it from Lebanon. A year later, the contents of the Center’s library were returned by Israel to the Palestinians via Algeria, as part of a prisoner exchange deal through the Red Cross.

Now, 40 years later, after a convoluted story, the Center has been reopened in Ramallah, although I am long retired. Its library is on its way back from Algeria to the Center’s new location. Although the current environment is far from Beirut in the 1960s and 1970s, when the Center was at the forefront of a revolutionary struggle, there is an ongoing attempt to revive some of the Center’s work in research and publication.

In terms of Zionist hostility and aggression towards Palestinians, I don’t see a great difference between then and now. This has persisted and, in fact, has escalated and become more damaging, painful, and racist. As Palestinians, we are still trying to inform the international community of our plight, although our cultural institutions, like everything else, have come under relentless attack. Israel is particularly aggressive towards Palestinian cultural activity; in the past, it assassinated tens of writers and intellectuals, and today, it continues this trend in its widespread killing of journalists. Writers, intellectuals, journalists, even artists – they all pose a threat to Israel because they expose its crimes against the Palestinian and Arab people.

LA: You have dedicated much of your life to the study of Zionism and have also experienced its savagery and destruction very directly. Given all of that accumulated knowledge and life experience dealing with Zionist violence, have even you been shocked by the length and scale of the genocide ongoing in Gaza, or given what you know, did you feel that it was always possible such horrors would take place?

SJ: The aggressive nature of the Zionist project towards the Palestinians and the Arabs has never diminished. This is due to the Zionist premise that the Palestinians must leave the country, in order for Israel to seize it as a whole. This aggression has been part and parcel of the Zionist movement from its inception until today. During the course of this movement, tens of projects were proposed for the expulsion of the Palestinian Arabs from their land. This was an ongoing, core tenet discussed in the Zionist project – only changing in form, from one Zionist venture to the next.

Documenting history, and especially racist atrocities, is very important. This gives future generations accurate, documented information on the events that have transpired, and would greatly help, one day, to restore the rights to their owners.

In 1948, the Zionists managed to empty more than two-thirds of Palestine of its inhabitants. This was engineered and planned more than two years before the establishment of Israel, as evidenced by Plan D, which was put in place in 1946 by the Zionist leadership in Palestine, on how to conquer the country, or at least the parts that might be allocated to the Jewish state in the UN Partition Plan. Plan D was then executed fully by Zionist militias, driving away Palestinian inhabitants, turning them into refugees, occupying their villages, destroying them and removing the remains, changing the nature of the land and establishing Jewish settlements under new names on it. On the sites where settlements could not be established, the lands were planted with trees and turned into forests. In the towns and cities, Palestinian properties were handed to new Jewish immigrants. This was a process of complete ethnic cleansing.

Given all this, however, I am still shocked by the amount of brutality and deep genocidal acts of Israel against the Palestinians in Gaza, because the extent of death and destruction has totally eclipsed all the disasters that Israel has inflicted on the Palestinians since the Nakba. The deep-seated racism and dehumanization underlying these horrors seems to mirror, to a large extent, the premises of the German Nazi regime against the Jews in the holocaust – and are even more shocking, as a result.

LA: At a time when many feel despair and are demoralized by the genocide in Gaza and Zionist expansionism and violence elsewhere, why does rigorous empirical research remain important? What can it contribute to the struggle against injustice generally and the Zionist occupation of Palestine specifically? Has your opinion on this changed since your research and writing first began?

SJ: Documenting history, and especially racist atrocities, is very important. This gives future generations accurate, documented information on the events that have transpired, and would greatly help, one day, to restore the rights to their owners. Also, it provides a lesson, to all those with good intentions, on how to prevent such atrocities in future. And, possibly, it may help stop their recurrence.

All over the world, there is a deep trend of digging into history to uncover the truth for all nations and all countries – a worldwide body of historical research that only keeps growing. In my conviction, I do not deviate from this body, but think I am part of it. Everyone is now researching history or geography, especially atrocities, as various nations try to come to terms with their past.

In my opinion, one should never give up; silence on such atrocities is in itself a crime and a failure to perform one’s duty. In the case of Palestine, all that has happened recently has been comprehensively documented, due to modern, advanced technology, in a way that has never happened before in our history, and it can never be obliterated. Future research will have an abundance of material to draw on, to expose the Israeli and Zionist crimes against the Palestinian and Arab people.

LA: It is hard to imagine now, but your study, The Arabs in Israel, originally published in Hebrew in 1966, was so seminal in part because there was such a profound lack of awareness about the repression faced by those Palestinians that Zionist forces were unable to expel from what they declared ‘Israel’ in 1948. In the six decades since you wrote that important work, how have things changed for this internally oppressed Palestinian population? How do you think the experience of the Palestinian youth inside ‘Israel’ today differs from your own experience growing up?

SJ: Israel’s attitude towards its Palestinian Arab citizens has not fundamentally changed. Since 1948, they continue to be considered second-class citizens and are treated as such. The difference is that, in the first years after the founding of the state, the measures were vulgar and openly oppressive (a practice which was transferred, since 1967, to the West Bank and Gaza). After the Nakba and the founding of Israel, its remaining Palestinians, whom it did not manage to expel, were immediately placed under direct military rule, where their movements were restricted, their sphere of work was limited, and their means of resistance were tightly curtailed. The change came after 1967 and the occupation of the remainder of Palestine (the West Bank and Gaza). It was important for Israel to divide the two sectors of the Palestinian people, such that they would not coalesce into a natural unit. Thus, it moved its repressive measures from its own Palestinian citizens to those in the newly occupied territory. The main aim was to prevent a situation in which the Palestinians in Israel would identify with their brethren in those areas – thus, keeping the Palestinian citizens of Israel isolated and forbidding the formation of a united front against Israel’s occupation. Yet, despite the removal of its military regime from its Palestinian citizens, Israel never looked at them with equality.

Today, its oppression against them is simply more sophisticated. It takes the form of cleverly concealed laws of discrimination, trying to contain this population. But times have changed. The Arab minority of 170,000 in 1948 has grown to be more than 2 million, with a big change in their social structure. Now, there are thousands of professional and intellectual Palestinians in Israel, in all walks of life, and it is difficult for the regime to ignore them. One example is very striking: the ratio of Palestinian Arabs in the medical system, which exceeds their ratio among the population. Palestinian Arab pharmacists, for example, dominate the profession in Israel. During the COVID-19 epidemic, it was said that if the Arab employees in the Ministry of Health went on strike, the state would collapse. However, a mass uprising among the Palestinians in Israel has not transpired. Several reasons may be at play. The livelihood of this community is intricately woven into its status as Israeli citizens, and many fear the backlash on their lives and families. Since the war on Gaza, the Israeli state has built a complete web of repression amounting to near fascism; people have lost their jobs, schooling, and been imprisoned for voicing protest or dissent. Israel has also, as noted above, worked hard – and seemingly succeeded – in breaking up the pillars of the Palestinian community and creating a sense of separation among Palestinian citizens of the Israeli state from their brethren in the West Bank and Gaza. Yet, many Palestinians in Israel are bitter and enraged about what is going on – but have no avenue to voice their feelings.

At the same time, these Palestinians, born after the founding of Israel and who grew up as citizens of it, have a deep awareness of the discriminatory laws of the Israeli regime against them, and find multiple ways of circumventing them. Far from my time as a young man, when people were afraid of the military rule and largely ignorant of the calculated government policy, the Palestinian Arab society in Israel has today changed, openly coming forth to challenge the policies and practices of the state when they are directed against it. This has been a long and bitter struggle, while the struggle against Israel’s war and ethnic cleansing in Gaza and the West Bank remains largely missing or subdued – as I noted above.

LA: The publication that we have worked on together, The Foundations of Zionism, originally published in two volumes in Arabic in 1977 and 1986, has a fascinating backstory; could you say a little about that and the research it entailed? What had you hoped would come of the book then, and what do you hope can come of it now that it’s reaching new audiences through this English language translation by your daughter, Fida?

SJ: Since my days as a university student, as I came to understand what was going on, I was struck by the prevailing Arab ignorance of Israel and Zionism. I thus thought that researching these and writing about them in Arabic would serve the Palestinian cause and the Arab one, in general. There was no shortage of material on the subject, and I was greatly helped by having studied at an English high school in Nazareth, then in the Hebrew University, in Jerusalem, such that I had a knowledge of the three languages in which the sources of Zionism could be found: Hebrew, English and Arabic. These tools were key to my endeavour.

The oppression I experienced at the hands of the Israeli regime, and the restrictions it placed on me, were a main motive for me to discover the perverse Zionist mentality and its manifestations in the founding of this regime. An opportunity presented itself when the regime internally expelled me to Safad, in the Galilee, in 1965, because I had “dared”, with some fellow activists in the al-Ard movement, to want to run for a seat in the Knesset (Israeli parliament) in the upcoming elections. The expulsion order separated us, as a group, and prevented us from organizing or taking part. Per the order, I was forced to remain in Safad for three months. While walking in the town, which had been completely depopulated of its Palestinian people during the Nakba, I chanced upon a small bookstore, in which the Jewish owner sold some books of the founding fathers of Zionism. These books helped me to fill the gaps in my knowledge, and the notes I made formed the blueprint for this book, which was eventually published in Arabic, in Beirut and then in Cyprus.

The aim of this English translation, today, is to expose the Zionist fallacies and correct their forgery of history, to the reader. The first point is to rebuff the Zionist claim of being a national liberation movement and, rather, to describe it as it is, namely, a Western colonialist movement that formed and crystalized during the peak of Western imperialism in the second half of the 19th century. The second point is to explore the Zionists’ role in selling themselves as agents of Western colonialist powers and their attempts at hegemony in the Middle East. A third point, supported by the research in the book, refutes their claims that the Jewish people, for millennia, always “yearned for” Palestine, or the “Land of Israel” as they term it. In fact, for 17 consecutive centuries, no Jewish group, anywhere, made an attempt to return to this land. Zionism arose out of an exclusionist, separatist tendency among the Jews of eastern, and later western, Europe, who feared their assimilation with the peoples that they lived with and considered their Jewish religion to classify them as a separate “nation”.

My hope is that this book will reveal this Zionist nature and conspiracies with colonialism, as The Arabs in Israel revealed the treatment by Israel of its Palestinian citizens.

Sabri Jiryis

Sabri Jiryis is the author of The Foundations of Zionism (Liberated Texts/Ebb, 2025). He is a Palestinian scholar, lawyer and writer. An Israeli citizen who lived through the Nakba as a child, he graduated from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and dedicated his life to the study of the Palestinian cause and Zionism. He served in the Palestine Liberation Organization as director of its Research Center, member of the Palestine National Council and Fatah Advisory Council, and advisor to Yasser Arafat on Israeli affairs.

Louis Allday

Louis Allday, a historian, writer and editor, is the Founding Editor of Liberated Texts and Series Editor of a collaboration between Liberated Texts and Ebb Books. This series published the first English language translation of Ghassan Kanafani’s On Zionist Literature, in 2022, to mark the 50th anniversary of his assassination by Israel. Next in the series is Sabri Jiryis’ The Foundations of Zionism.